Posted November 27, 2025

By Byron King

What the Pilgrims Found at Plymouth Rock

Happy Thanksgiving. Today, Sean handed me the car keys and said I could drive. “Just don’t wreck it,” was his parting plea.

Okay, first… From Paradigm Press, we wish you well and thank you for subscribing to our newsletters, which is why you receive the Rude on top of everything else. We hope you, your family, and friends have a great day.

Now, down to business… Let’s discuss gold, precious metals, energy, mines, mining, and making money. But first, I have some thoughts about Pilgrims, Thanksgiving, and wealth creation.

Pilgrims land at Plymouth Rock, 1620. Courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Pilgrims land at Plymouth Rock, 1620. Courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Settlers and What They Found

America’s Thanksgiving dates back 404 years to 1621, when a group of settlers called the Pilgrims arrived on a small sailing ship called the Mayflower. I’ll skip the details except to say that the overall history has changed greatly over time. And indeed, one perplexing thing about American history is how often it changes, depending on fads and fashions.

Still, let’s time-travel back to December 1620, the year before that first Thanksgiving, to when those Pilgrims first landed at Plymouth Rock, in eastern Massachusetts, just north of Cape Cod.

Plymouth, Massachusetts. Courtesy Encyclopedia Britannica.

Plymouth, Massachusetts. Courtesy Encyclopedia Britannica.

What did the Pilgrims find when they stepped off the boat?

They found rock! Supposedly, this one, and no, I’m not kidding.

Plymouth Rock. Courtesy Dept. of Conservation & Recreation, Commonwealth of Massachusetts.

Plymouth Rock. Courtesy Dept. of Conservation & Recreation, Commonwealth of Massachusetts.

This is Plymouth Rock. And to my highly trained geological eye – trained at Harvard, located in Massachusetts, no less! – this thing looks like a glacially rounded boulder. That is, it’s what we call “float stone” that, more than likely, was precipitously deposited during a widespread melt-phase when the last Ice Age ended about 10,000 years ago.

No doubt, and as a matter of pure, black-letter, first-year college geology, Plymouth Rock rested upon other rock, plus sand, loam, and other materials that form the bedrock of coastal New England.

According to the Smithsonian Institution, the original Plymouth Rock weighed more than 20,000 pounds. But over time, through the 18th and 19th centuries, souvenir hunters chipped it down, although no pieces have been noticeably removed since 1880.

At any rate, let’s get back to the Pilgrims who landed on a cold, damp, stern, windswept coastline. Whatever they thought or sought, the fact is that both literally and figuratively, they found rock.

Apparently, they found this Plymouth Rock specimen, and no doubt, indeed, many more rocks much like it. Because the world is made of rock. That is, rock, rock, and more rock. Okay, and in New England at that time, the land was covered with trees, trees, and more trees.

In other words, when Pilgrims arrived on the continent, North America was undeveloped and, for the most part, a raw wilderness. Sure… there were people here already: Stone Age natives who eked out a tough life amidst the rocks and trees. But the point remains that the landscape was undeveloped in any meaningful sense. Human alterations were negligible, just a few clearings, some burial mounds, and primitive log buildings here and there.

Meanwhile, the calendar did not favor the Pilgrims. They landed in December, just as one of those legendary, totally miserable, awful New England winters was kicking off. Then as now, New England inflicted brutal weather on its inhabitants, which proved to be fatal to many new arrivals. Indeed, out of 102 Pilgrim passengers who debarked from the Mayflower, 45 died in the first year, mostly of scurvy and exposure.

A decade later, Pilgrim leader William Bradford described the newfound American landscape as “hideous and desolate,” full of “wilde beasts and wilde men (sic).” But there was no turning back. A transatlantic voyage was, in those days and for most people, a lifetime commitment, and that’s if the ocean itself didn’t kill you along the way.

Bradford and his clan viewed their new home as a place of trial and testing; certainly not a place of ease and plenty, let alone social and economic opportunity. Oddly enough, though, and despite the harsh terrain and climate, Bradford also described the countryside before him as a New Eden or a New Jerusalem, where the teachings of Jesus Christ would prevail and the exalted Millennium would take place.

But first, of course, Bradford and his Pilgrims had to avoid dying of hunger and/or freezing to death. They had to build shelter, generate heat, find food and potable water, and basically not vanish into the dust of myth and legend.

Looking back, despite their iconic place in American history, the Pilgrims and their Plymouth settlements were, in many respects, a failure. Unlike what happened just to the north, in what became Boston, Plymouth lacked a deep-water harbor (aka, in geology, “a post-glacial drowned river valley”) suitable for sea-going vessels. Nor was there any river that led upstream to the interior to provide access to the native Indians and their fur trade.

Plus, the soil around Plymouth was thin and poor, underlain at shallow depth by glacially polished solid bedrock. Hence, for all their efforts, the Pilgrims could accomplish little more than bare-bones subsistence farming. And a year later, supposedly in 1621, the surviving Pilgrims shared a meal with a few friendly natives; hence, the idea of Thanksgiving was born.

Settlers, Builders, and Creators of Wealth

Long ago, China’s Confucius emphasized the importance of calling things by their correct name. And in that sense, let’s be careful to describe those old Pilgrims as “settlers.” That is, they were not so-called “immigrants” because settlers come to settle in and build, while immigrants arrive in a place that already has something established. (For example, note the immigration lines at U.S. and Canadian airports.)

And back in 1620, North America had nothing with which to greet the new arrivals at Plymouth Rock... well, other than rocks and trees, right?

Then everything that followed the Pilgrims – the development of North America; the creation of vast wealth – occurred because other new arrivals, almost all of them from Europe (and Africa, of course, although nearly none by choice), built and developed what was around them.

That is, people chopped trees and moved rocks to build roads, fences, farms, barns, homes, and workshops. They produced energy from wood fires, built water dams on streams, and eventually figured out coal. Plus, they found minerals with which to produce metals, certainly iron for tools, and even resources with which to make items out of copper, tin, and zinc; alloys like bronze and brass.

In this respect, everything that has happened in North America over the past 404 years occurred because people settled here and built it out. And ponder, if you will, how phenomenally tough a job that was in the early days when all that was available was… well… rock and trees. C’mon, ask yourself… Could you have done that? Yeah, good luck. Grab an axe or a sledge and let’s get to chopping.

Keep in mind, too, that much of North America’s early settlement was pre-industrial age. As in… the Pilgrims showed up in 1620, and England’s James Watt, for one example, didn’t invent the very useful steam engine until 1769. That’s not quite a century and a half post-Pilgrims before even the idea of “horsepower” meant more than literally a horse pulling a wagon or plow. And the Pilgrims didn’t have horses!

Or consider that it wasn’t until 1859, not quite a quarter millennium post-Pilgrims, when Colonel Drake drilled North America’s first commercial oil well at Titusville, Pennsylvania. He thus inaugurated the oil age, an era whose hallmark is significant amounts of very useful energy and chemical feedstock stored within petroleum.

Here’s where this idea-string is taking us: begin with rocks and trees; then energy, minerals, metals; and then even more energy, more minerals, more metals; and we wind up with all sorts of useful things that we pretty much take for granted these days. And if you don’t believe me, try losing your smartphone for an hour or two.

Meanwhile, something else we’ve inherited from the Pilgrims is a dour sense of suffering, a trademark of New England’s early religious formation. Consider the Puritans, who encamped north of Plymouth Rock and who were not happy until everyone was unhappy, a school of thought now enshrined in national-scale Nanny-State politics across the U.S.

And consider what has happened to American culture (such as it is) in the wake of the discovery that the federal government can just emit currency and make claims on real wealth. Say what you want about those early settlers, but they gave rise to habits of hard work, thrift, prudence, productivity, and more. As in… Benjamin Franklin of the 1700s, for example, whose legacy speaks for itself.

Wrap Up

Okay, enough discussion of Pilgrims, settlers, and the idea of how to create wealth out of rocks and trees. Now, let’s look at some ways to hang onto it. And that means investing in the future upside of gold prices.

One way to hang onto your wealth over time is through gold royalty companies, of which there are many. Right now, I like Osisko Royalties, Inc. (OR), with a market cap of $6 billion and a share price around $32, down from recent highs and a relative bargain as compared with peers. It’s well run and diversified, with a mix of projects and a broad geographic footprint.

Another royalty play I like is smaller but positioned to become takeover bait in a rising gold market. That’s Empress Royalty Corp. (OTC – EMPYF), with a relatively small market cap of $100 million and a share price around $0.80, again down from recent highs. But much like Osisko, Empress is well run, with a strong book of projects spanning a variety of jurisdictions, each at varying stages of development or operations. There’s upside here.

Finally, I’ll give a plug to the Sprott Junior Gold Miners ETF (SGDJ), with a market cap of $275 million and a share price around $73. This is a professionally managed fund of 25 different junior mining plays, all with solid management and significant exploration and development upside, certainly in the current strong market for gold and mining plays. Owning an exchange-traded fund (ETF) like this eliminates the problem of stock picking among junior companies while still offering exposure to a strong part of the sector.

To be clear, these names are not part of any official Paradigm Press portfolio. Instead, they’re ideas that I think have merit and upside in the current gold environment. If you buy shares, be sure to watch the charts, wait for down days in the market, always use limit orders, and never chase momentum. That, and be patient while America’s ongoing monetary circumstances play out. We’ll have up days and down days, but for gold, the best days remain ahead.

There’s always more to say, but that’s all for now. Thank you for subscribing and reading.

And again, remember those Pilgrims and have a Happy Thanksgiving.

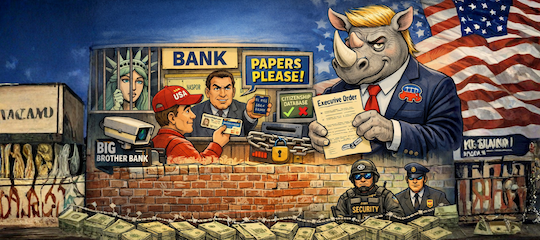

The Biggest RINO of Them All

Posted February 27, 2026

By Sean Ring

Sports, Predictions, and Morons

Posted February 26, 2026

By Sean Ring

SOTU or STFU?

Posted February 25, 2026

By Sean Ring

Building an AI-Proof Portfolio

Posted February 24, 2026

By Sean Ring

Beware of Flying Turkeys

Posted February 23, 2026

By Matt Badiali