Posted November 11, 2024

By Sean Ring

Veterans’ Day: War, Peace and President-Elect 47

Banks are closed. No mail delivery. Perhaps there’s a parade downtown, near where you live. Yes, it’s Veterans’ Day, recalling the armistice that ended the Great War – aka World War I – at 1100 hours Continental time, on 11 November 1918.

That date seems long ago, but we still live in the world that the war created. The conflict broke Europe and its culture. It broke empires. It created a massive U.S. government credit system and provided Woodrow Wilson with his excuse to inflict Big Government across America. Hey, people write books about things like this.

But I’ll offer no book here. Just a morning note to highlight the Veterans’ Day date and then, to use a Trumpian term, “weave” a discussion about last week’s election outcome, along with other items that strike me as pertinent.

Trump 47

He’s president-elect again, and even the New York Times admits it. Plus, to the great benefit of the now older, wiser, almost-assassinated man from Queens, he’ll have a Republican Senate to confirm his appointees and nominees.

There’s much to say about what just happened. But let’s narrow things down to one fundamental item, the matter of war and peace. That is, consider how, anymore, we routinely hear serious people say that the world is “on the cusp of World War III,” or how this or that conflict (there are more than one) “could go nuclear.” Obviously, this should worry us.

Money comes and goes. Stock markets rise and fall. But when you distill things to an essence, the prospect of major war should focus the mind. Or to cite a line that’s often attributed to Leon Trotsky, “you may not be interested in war, but war is interested in you.”

During the first Trump administration (2017 – 2021), we had no new wars. Yes, skirmishes here and there; some missile strikes, to be sure. But in general, Trump kept the dogs of war at bay.

As the Biden-Harris administration winds down, we now have ongoing conflicts between Ukraine-Russia, Israel-Iran, Houthis in Yemen versus Western shipping, and volatile tensions of China-Taiwan; as a result, U.S. weapons and doctrines are everywhere in play. Our national interests are set up for high risks from a long list of potential disasters.

Meanwhile, the U.S. defense budget is gigantic, north of $840 billion this year. And yet, for all that money, it’s not enough. An entirely new set of budget demands about to hit the spending accounts, and Team Trump faces a defense spending blowout. So 47 and his inner circles will have to figure out how to make it all work.

On the brighter side, this new government spending Niagara is investable, and further along I’ll mention programs with upside. But first, I want to tell you about my recent travels.

When War Changed Within Microseconds

Not long ago I visited a place called Trinity, in the middle of New Mexico. And perhaps that name rings a bell. It’s where the U.S. detonated the world’s first atom bomb in July 1945.

More recently, in 2023, the movie Oppenheimer presented a broad Hollywood version of what happened there, before and after. But like all movies that cover big subjects, the producer and director left much on the cutting room floor.

The Trinity site is located on a highly restricted military installation. It’s a national historical locale, now marked by an obelisk constructed of black basalt. But at the same time, it’s sealed off from the public and guarded by guys with machine guns. Still, for a few hours on just one day per year, the Department of Defense allows a relatively small number of people to enter this isolated stretch of real estate, walk around and have a look.

Your editor at Trinity, Ground Zero. BWK photo.

Your editor at Trinity, Ground Zero. BWK photo.

On the third Saturday of this October, one of those people walking around at Trinity was me. In fact, I stood at the exact spot where, beneath what used to be a 100-foot steel tower, the Army conducted the world’s first nuclear explosion. The device was put together pursuant to a top-priority national effort in World War II called the Manhattan Project.

World’s first nuclear explosion; July 16, 1945, at Trinity. Courtesy Department of Energy.

World’s first nuclear explosion; July 16, 1945, at Trinity. Courtesy Department of Energy.

It’s not easy to get onto the Trinity grounds; I spent two years on a waiting list and had to submit a checklist of personal information to the facility security manager. But there’s much to gain from visiting the place. There’s something to be said just to go there, take in the sense of it all, walk the grounds and feel the sand crunch beneath one’s boots. (Hold that thought about “sand.”)

Here’s what happened at Trinity, courtesy of the Los Alamos National Lab, where much of the first atom bomb was developed:

“An incredible flash of light illuminated the sky as air temperatures rose to over 9,000 degrees Fahrenheit. Within seconds, witnesses saw the first mushroom cloud ever created by atomic weaponry. To most observers—watching through dark glasses—the brilliance of the light from the explosion overshadowed the shock wave and sound that arrived some seconds later. A multi-colored cloud surged 38,000 feet into the air within seven minutes. Where the tower once stood was a crater one-half mile across and 8 feet deep. Sand in the crater was fused by the intense heat into a glass-like solid, the color of green jade. This material was given the name trinitite. The explosion point was named Trinity Site.”

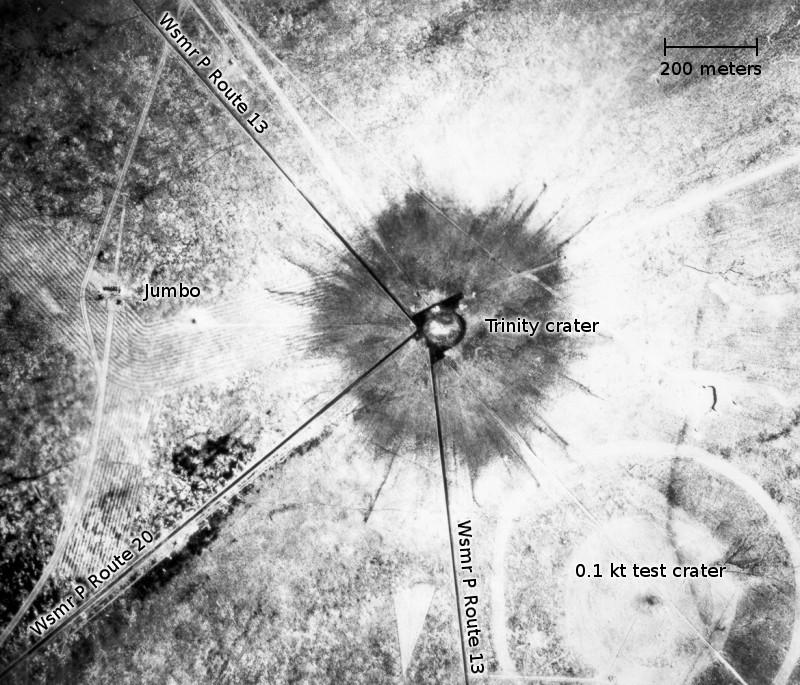

And here’s an aerial photo, taken the day after by an Army reconnaissance airplane:

Trinity blast site and crater. Courtesy Department of Energy.

Trinity blast site and crater. Courtesy Department of Energy.

As for that above noted trinitite material, here’s an image of one small chunk:

Trinitite, a nuclear-melted form of glass. Courtesy Stanford University. Most trinitite is a greenish glass (although to be thorough, some is reddish, black or brown; the chemistry varies). Technically, it’s an “amorphous solid” which means that there’s no crystal structure to the atoms inside. That is, the nuclear blast vaporized sand on the desert floor, which then evaporated into the fireball. Over a short amount of time, temperatures in the fireball dropped, and these elemental vapors formed into smallish glass globs that essentially rained down from the mushroom cloud to the surface.

Trinitite, a nuclear-melted form of glass. Courtesy Stanford University. Most trinitite is a greenish glass (although to be thorough, some is reddish, black or brown; the chemistry varies). Technically, it’s an “amorphous solid” which means that there’s no crystal structure to the atoms inside. That is, the nuclear blast vaporized sand on the desert floor, which then evaporated into the fireball. Over a short amount of time, temperatures in the fireball dropped, and these elemental vapors formed into smallish glass globs that essentially rained down from the mushroom cloud to the surface.

Right after the blast, the Trinity crater was filled with this greenish trinitite stuff. And way back then, in the olden days, visitors and government employees snagged samples, which over time made their way into mineral collections (including mine). Anymore, it’s illegal to collect trinitite samples at the site. So, if you want a specimen, you must find the right rock shop, or maybe keep an eye on eBay.

Trinity and the Jornada del Muerto

Now, for just another moment, let’s add a bit more history. Why did Robert Oppenheimer and his Manhattan Project colleagues decide to test their bomb out in this particular stretch of New Mexico desert?

The answer begins long ago in the 1550s, when Spanish conquistadores arrived in the region. Today, we call it central New Mexico. More precisely, those old soldiers were west of what is now Alamogordo and Holloman Air Force Base. They explored across a vast area of flat, dry, desolate outback that now comprise the Army’s White Sands Missile Range.

Of course, there were no roads back then; just a few, scattered native trails that wound through broken rock, patches of sand, clumps of stinging plants, and nests of rattlesnakes and scorpions.

The landscape of Trinity, aka Jornada del Muerto. BWK photo.

The landscape of Trinity, aka Jornada del Muerto. BWK photo.

Cautiously, as you can likely imagine, the Spaniards moved ahead on foot or horseback. They trekked south to north across a vast, harsh, rocky flatland between two mountain ranges. All in all, the crossing covered about 160 miles and at the end of the trail, the explorers named the region Jornada del Muerto, loosely translated as the Route of the Dead Men. If you look around the locale even today, it’s not hard to understand what the Spanish were thinking. The place can kill you.

Seriously, it’s hard fully to describe the desolate nature of this stretch of land, the starkness and isolation. Except that the level of remoteness is exactly what the U.S. government was looking for during World War II, when the Army and Navy needed a training range where pilots could practice dropping bombs. And so, a large amount of the landscape in the area became a government military reserve.

Then in 1944, the above-mentioned Oppenheimer realized that he needed a place to test his new invention. And so, from a list of numerous possible sites that ranged from California to Texas, the atomic scientist chose this place, Jornada del Muerto.

One wonders what was going through Oppenheimer’s head when he gave the name Trinity to part of an old landscape described by the Spanish word for death, because the name has religious connotations. Trinity is the Christian Godhead, meaning one God in three persons: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.

Oppenheimer’s goal was to build a bomb and cook it off, to see what might happen. Then again, there’s a certain religious symmetry to it all.

From Trinity to a New Trinity

Collectively, Oppenheimer and his team (at least, those in the top elements of the Manhattan Project group) understood that they were constructing a weapon of great power. And as the historical narrative goes, per the official Los Alamos history, when the nuclear scientist witnessed the first detonation of his weapon, a piece of Hindu scripture ran through his mind: “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds;” a sentence that is, perhaps, the most well-known line from the Bhagavad Gita.

To shorten many decades of events into a few words, out of everything that occurred at Trinity – out of that successful test blast – grew the nuclear armed Cold War, 1945 through… Well, it sort-of ended in 1991 with the collapse of the Soviet Union; but now it’s rebooting.

That is, I’m sure that many subscribers are old enough to recall their upbringing in the 1950s, 60s, 70s or 80s. You lived through the Cold War between the U.S. and Soviets, with civil defense drills in schools, and routine discussions of how many bombers, missiles, submarines and weapons each side had in the arsenal.

In both the U.S. and Soviet Union, each government devoted immense levels of money, energy and resources to building nuclear weapons and ways to drop them on the other side. And again, we’ll skip the vast details of history, other than to recall a phenomenal national commitment to those bombs and delivery systems.

Which brings us to now, when the U.S. is about to engage in another similar effort, because America’s Cold War nuclear systems have aged-out into an expensive collection of legacy articles. It’s a so-called “triad” of land-based missiles, submarines and sea-based missiles, and aerial forces to deliver nuclear weapons; plus, the nuclear weapon packages themselves. And all of them are at or near the end of their lifespan. It’s block obsolescence for the nukes.

For example, America’s B-52, B-1, and B-2 bombers are old and wearing out, despite immense levels of maintenance. The land-based Minuteman missiles are similarly antique, as these things go, and are decades beyond their 1960s-era design life. While the Navy’s missile-launching Trident submarines are still out there, on patrol but with a life expectancy that’s plotted on relatively short timeframes.

All of this brings us to the intersection of the recent election and geostrategic reality. Because as of January 20, 2025, Trump 47 will immediately have critical decisions on the desk: Can the Air Force deliver on its programs for new intercontinental missiles, plus a brand-new bomber? Can the Navy deliver on its Trident-replacement program, now called Columbia, named after the lead ship of the class that’s been on the drawing boards for a decade or more?

Earlier, I mentioned that the defense budget is in the range of $840 billion this year. But that’s before even larger sums must be spent to buy and build the next generation of nuclear delivery systems and bombs, those “strategic” weapons.

Sad to say, the Air Force program for a new-land based missile is far over budget, whatever may be the technical merits of the upgraded design, led by Northrop Corp (NOC) with many subcontractors.

Meanwhile, that same Northrop company is in the early stages of testing and producing a new bomber called the B-21. And the price tags for everything, anymore, rings the cash register in numbers like multi-hundreds of millions per unit, with some systems totaling into the billions. So yes, it’s big money is in play.

Meanwhile, the Navy has been diligent with the Columbia class submarine. The timetable is unforgiving to replace the aging Tridents. The main builder will be General Dynamics (GD), with a large body of work from Huntington Ingalls Industries (HII), plus many subcontractors. But again, sad to say, costs are climbing, and schedules are slipping, although the first vessel is due to get wet in 2028.

There’s much more to say about the U.S. defense budget. For now, suffice to say that the flow of funds for strategic programs will be immense, up and down the vendor and supply chains. Some people will make seriously big money out of all of this, and we’ll follow it in the future, here in the Rude and in Strategic Intelligence.

With that, I’ll sign off from the Veterans’ Day note, and wish you well as history unfolds in the wake of our 2024 presidential election, bringing back Donald Trump for another term in office.