Posted September 24, 2025

By Dan Amoss

The Duke, the King, and the Great Auto Loan Con, Part I

When Mark Twain introduced the Duke and the King in The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, he created two of literature’s most vivid portraits of swindlers.

The pair drifts down the Mississippi River with Huck and Jim, staging schemes that prey on human gullibility and greed.

They pose as Shakespearean actors, royal heirs, even pious preachers. Each ruse is more elaborate than the last.

“It was enough to make a body ashamed of the human race,” Huck observes, after watching townsfolk hand over their money to these impostors.

Twain’s story is not only a satire of small-town America; it’s a parable for financial products that cloak risk in over-engineered complexity.

The Duke and King were selling the equivalent of faulty structured products long before Wall Street gave the term currency. Today’s equivalent is the asset-backed security (ABS), a package of loans sold to investors who often rely on intermediaries’ word – and rating agencies’ stamps of approval – that the risks are contained.

But as the recent bankruptcy liquidation of subprime auto lender Tricolor Holdings shows, the risks often lie hidden in plain sight.

The Theatrics of Risk

The Duke and King thrived by wrapping simple cons in the trappings of sophistication. One moment, they staged a clumsy production of Romeo and Juliet. Next, they claimed noble titles, their accents and airs convincing enough for the gullible. Their marks wanted to believe, and so they suspended disbelief.

Structured finance operates on similar stagecraft.

A bundle of subprime auto loans, many owed by borrowers without credit scores or driver’s licenses, can be transformed – through “tranching” and mathematical wizardry – into AAA-rated, income-yielding securities.

Investors, desperate for yield, play the role of Twain’s townsfolk, eager to believe they’ve found a safe bet with an advertised above-market return.

Tricolor perfected this theatrical transformation. The company’s June 2025 asset-backed securities deal, TAST 2025-2, featured borrowers with an average FICO score of just 600 – if they had credit scores at all.

Roughly 62% of the borrowers lacked FICO scores entirely, representing what industry euphemistically calls “credit-invisible” customers.

Yet through the alchemy of structured finance, these loans to illegal immigrants and credit ghosts were packaged into securities with 51.7% credit enhancement and favorable structural metrics. Credit enhancement means that, in theory, the pool of collateral is worth 50% or 100% more than the amount of money investors put into the ABS security.

The senior tranches carried investment-grade ratings. They are often so far up in the stack of creditor claims that they trade near par (100 cents on the dollar), like government bonds.

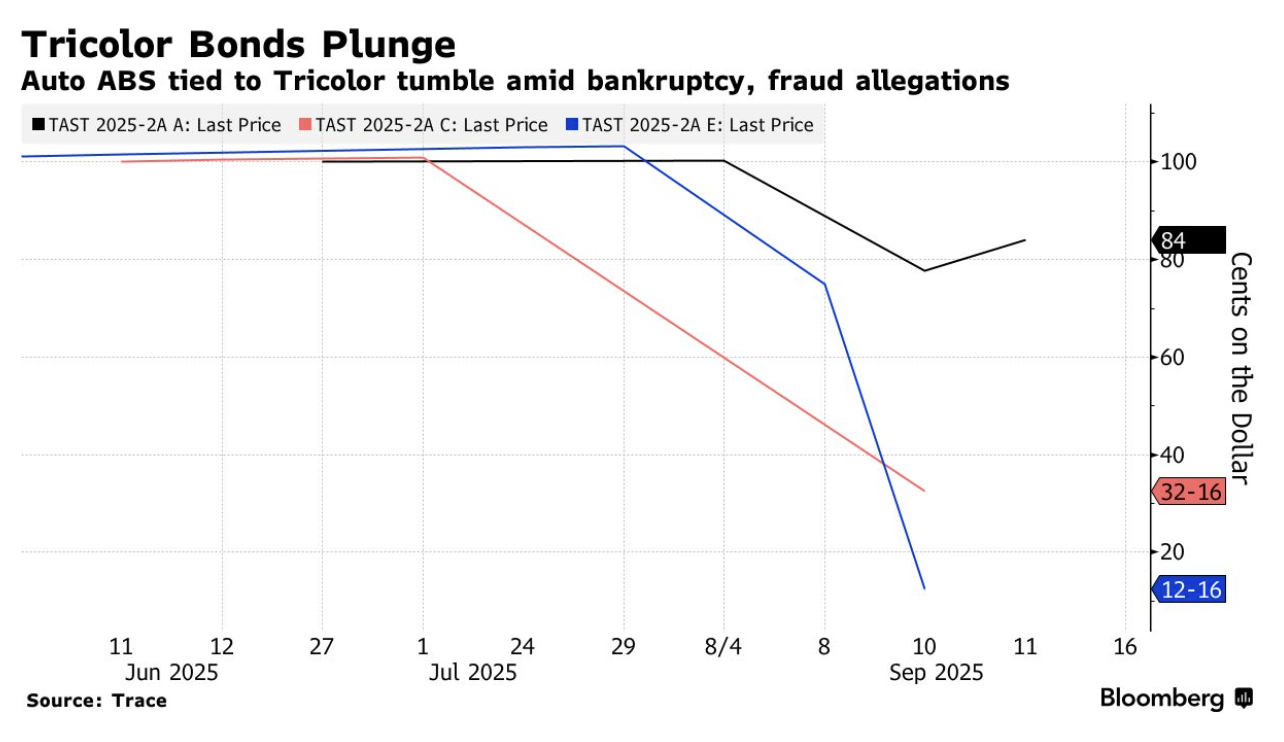

What is the mark-to-market price of TAST-2 (technically, the lower “E” tranche) now?

What is the market bidding for it now that the shenanigans have been revealed?

Twelve cents on the dollar – down from 100 cents on the dollar as recently as July. It’s shown in the blue line of this chart from a Bloomberg News story.

Even the senior “A” tranche is trading at 84 cents.

Before the revelation of dodgy collateral, the slicing and dicing of these loans was so convincing that KBRA, a major rating agency, actually upgraded Tricolor tranches in May 2025, citing “rising credit enhancement.”

Right up until the collapse, interest payments flowed on schedule, structural triggers remained intact, and the mathematical models hummed with satisfaction.

As credit expert William Black, a former Moody’s analyst, observed, “fraud is not the same as poor credit performance. You cannot underwrite against it.”

Like the King and Duke’s audience, who paid good money for a fake royal spectacle, investors discovered too late that the show had been an illusion.

The illusion was maintained – knowingly or unknowingly – because too many layers between lender and borrower were assumed to be modeled properly by mathematicians, or “quants,” who are often better off using their talents in hard sciences. The hard sciences are easier to model because greed and fear, naivete and fraud, are factors in every human heart. They are impossible to model.

Nassim Taleb, a sage critic of Wall Street securitization, has long warned against this sort of financial theater. In The Black Swan, he calls the Gaussian bell curve. Also known as the normal distribution, it’s the mathematical backbone of many risk models – “the great intellectual fraud.”

Risk in markets does not follow smooth, symmetrical distributions, Taleb argues. It lives in “Extremistan,” where rare, catastrophic events dominate outcomes.

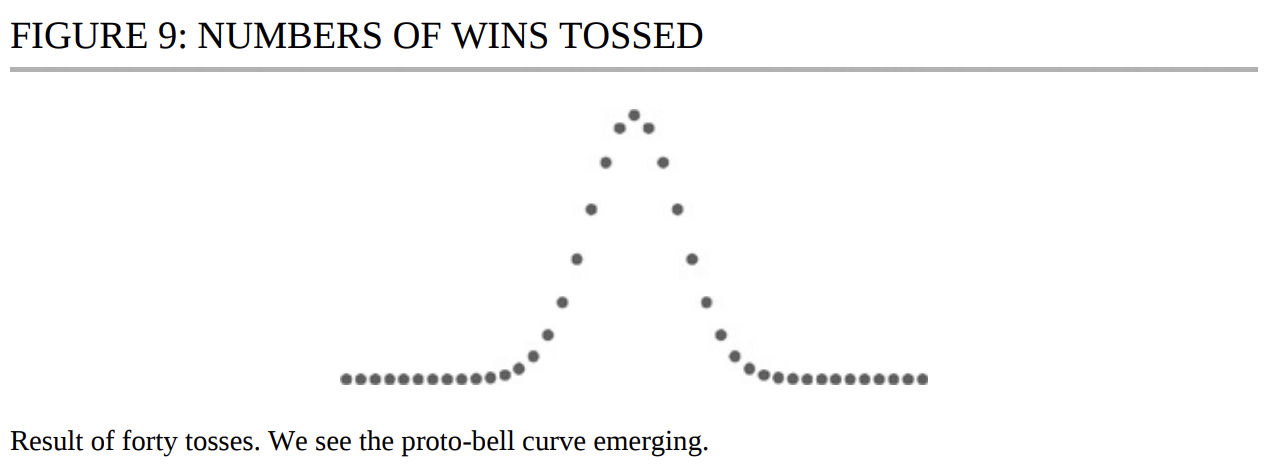

These visual presentations of the Gaussian bell curve from Chapter 15 of The Black Swan are from a coin toss experiment.

But real-life probabilities are not like coin tosses, so the bell curve gives a misleading impression of the remote event.

Such a remote event – like Tricolor underwriting auto loans with misleading claims on collateral – will be a point to the far right or far left of the center. But often, the event that’s modeled by quants as remote is much more likely.

“The Gaussian bell curve sucks randomness out of life,” writes Taleb, “which is why it is popular. We like it because it allows certainties!”

However, to dress up subprime auto loans with equations that suggest predictability or certainty of payment is, in Taleb’s words, to indulge in fictional mathematics built on “rigidly Platonic assumptions.”

From Subprime Cars to Human Follies

Tricolor Holdings specialized in loans to borrowers without Social Security numbers, often illegal immigrants. The firm packaged these loans into ABS and sold them to investors, with tranches ranging from senior, supposedly safe slices to riskier junior ones.

But the illusion ran deeper than anyone initially suspected. Federal investigators now believe the fraud was systematic and widespread, potentially stretching back months.

Bloomberg News poses the question: “Was there fraud, as federal investigators are now looking into, and how prevalent was it?”

Fifth Third Bank discovered that Tricolor’s master loan tape – the fundamental data file that lists information like outstanding balances, credit scores, and vehicle identification numbers – had been corrupted.

Banks are exploring whether the same vehicles were pledged as collateral to multiple lenders, a classic double-pledging scheme that would make the Duke and King from Huckleberry Finn proud.

The scope of the deception is stunning. Fifth Third faces impairment charges of up to $200 million. JPMorgan Chase and Barclays have similar exposures.

Triumph Financial dispatched security teams to used car lots across Texas, racing to identify and “whisk away to safe locations” the vehicles they believed served as collateral for their $23 million in Tricolor loans.

In Manhattan, boutique investment firm Clear Haven Capital Management began frantically calling other bondholders, urging them to band together before the big banks claimed assets that rightfully belonged to ABS investors.

Huck observed how easily the swindlers manipulated entire towns. The parallels to investors chasing yield in opaque securities are clear. Everyone sees the flimsy props and shaky stage, yet the prospect of return blinds them to the obvious risks.

More On The Mathematical Veil

The financial system’s equivalent of greasepaint and costumes is the layer of complex mathematics draped over structured products.

Nobel laureates Myron Scholes and Robert Merton popularized formulas that, in Taleb’s view, were built on sand.

In his book Antifragile, Taleb lambastes these approaches for amplifying errors rather than containing them. By assuming mild randomness – suited for “Mediocristan,” where small deviations average out – these models obscure the violent, nonlinear shocks of “Extremistan.”

This misapplication fosters a dangerous illusion: that risk can be neatly measured, packaged, and sold. But like Twain’s con men rehearsing lines they barely understand, the financiers employing these formulas often lack true comprehension of the forces they are dealing with.

The Tricolor case exposes how mathematical sophistication can mask fundamental structural vulnerabilities.

In most asset-backed deals, Tricolor served as both originator and primary servicer. It handled record keeping, billing, collections, and customer interface.

As William Black notes, this creates “a structural vulnerability: when the primary servicer is dishonest or collapses, the entire structure is reliant on the integrity of that party.”

All the safeguards – trustees, rating agencies, backup servicers – functioned as designed. Yet, they proved powerless against an unscrupulous actor who controlled the entire information flow.

The mathematics were elaborate, the documentation voluminous, the oversight extensive. Wilmington Trust served as trustee, Vervent stood ready as backup servicer, and KBRA provided ongoing surveillance.

But when the servicer corrupts the underlying data, these guardians offer a false sense of security. They verify the consistency of deceptive information.

(To be continued in tomorrow’s edition…)

A Minor Miner Correction

Posted October 03, 2025

By Sean Ring

$50 Silver: Ceiling or Floor?

Posted October 02, 2025

By Sean Ring

Equities and Metals Soar in a September to Remember

Posted October 01, 2025

By Sean Ring

Keep These Things In Mind When Riding the Wave

Posted September 30, 2025

By Sean Ring

Pennies and Steamrollers

Posted September 29, 2025

By Sean Ring