Posted June 08, 2023

By Sean Ring

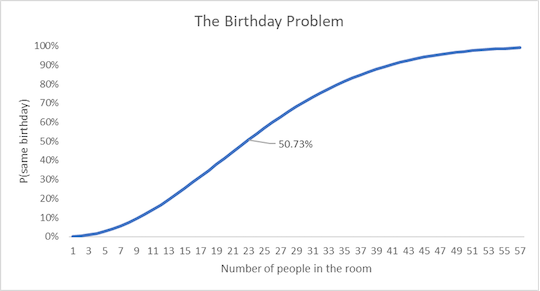

The Birthday Problem

- Beyond the simple mathematics lie statistics.

- But are we really good at stats?

- Let’s look at this issue that’s vexed the stats community since it was proven.

Happy Friday from the Big Orange!

We’ve been suffering the Canadian wildfire haze this week, but that hasn’t dampened our spirits.

The class I’ve been teaching with bosom bud Andy has gone well. The kids are from an absolute smorgasbord of the best schools in America. We’ve got Harvard, Michigan, Washington University in St. Louis, Penn State, Colorado, Colorado State, and my trusty alma mater, Villanova, among others.

And they’re really sweet young people, as well.

Andy was teaching about data and statistics when I chipped in with my favorite statistics problem.

It blew their minds, as it did mine when I first learned about it.

Since my mathy Rudes seem to go over well, I thought I’d share it with you.

The Question

When I interjected in Andy’s class (with his permission, of course), I asked one question:

What is the probability that at least two of you have the same birthday?

To be clear, we’re just looking for day and month, not year. So my birthday is December 20, 1974. We’d consider December 20, 1990, a match because we’re not looking at the year.

There are 229 students, 2 teachers, and five bank support staff in the room for a total of 236 people.

Now if you never heard of this famous problem before, you may offer something like “1 in a million” like I did. It’s not even close to the correct answer, as you’ll see.

To their great credit, the kids didn’t offer any outlandish answers like I did.

Most guesses were from “very low” to “50%” to “63%” to “very high” and “above 90%.”

I was impressed.

But the answer is 99.99999%.

Don’t believe it? I’ll prove it to you.

The Birthday Problem Explained

Before I show you the math, let me tell you what happened in class.

After I asked the question and got those very good answers, I said, “Now, let’s have some fun.”

I then asked, “Who has a January birthday?”

About 25 people raised their hands.

Then and there, I knew we’d have a match.

I pointed to a young intern, and asked, “What date were you born on?”

“January 17th,” she replied.

“Any of you with your hands up born on the 17th?” I asked.

One of the other interns had his hand up.

The class clapped uproariously.

I said, “Wow! The rabbit came out of my hat on the first try!”

The kids marveled.

Since I already knew the math, I wasn’t surprised at all.

The Math Behind The Birthday Problem

Alright, let's dive deeper into the math behind the Birthday Problem. Don't worry, I promise it won't be as daunting as it sounds!

The probability is easier to calculate if we consider the opposite: what is the probability that all people in a group have different birthdays?

First, consider an empty room and the first person who walks in. The probability that their birthday is not shared with anyone else (since they're alone) is 100% or 365 out of 365.

Now, the second person who comes in can have any of the remaining 364 days as their birthday to not share it with the first person. So the probability for the second person is 364 out of 365.

As the third person enters, they must avoid the two existing birthdays, so their probability is 363 out of 365.

As you continue this process, the probabilities keep declining for each new person.

So, for a group of 23 people, you'd multiply these individual probabilities together:

Let P = Probability.

P(all different) = (365/365) x (364/365) x (363/365) x ... x (343/365)

This comes out to around 0.4927, or a 49.27% chance that all 23 people have different birthdays.

But remember, we want the probability that at least two people share a birthday. So, we subtract the "all different" probability from 1:

P(at least one shared) = 1 - P(all different) = 1 - 0.4927 = 0.5073, or 50.73%

So, surprisingly, in a group of just 23 people, there's over a 50% chance that at least two people share the same birthday!

This is the surprising and counter-intuitive result that makes the Birthday Problem so fascinating.

For you traders out there, this means “take the bet” if there are 23 people in the room.

By the time we get to 57 people, the chances are just over 99% that two people will have the same birthday.

So with over 230 people in the room, the call was a no-brainer.

Here’s a chart of the Birthday Problem outcomes:

Credit: Sean Ring

I knew of the Birthday Problem because I read a book called Chance, by Amir Aczel, a long time ago.

Aczel was a statistics professor who wrote that little book because he was so frustrated at the innumeracy displayed daily. I share his opinion.

Aczel dedicated an entire chapter to the Birthday Problem because it’s so counterintuitive, even statisticians have trouble with it.

So don’t fret if you’re still trying to understand it. Professional mathematicians are still trying to understand it.

But more than that, it’s a reminder to not use our guts when it comes to financial decision-making. It’s important to think of the statistics behind our choices.

Wrap Up

Today’s short Rude is a reminder we don’t know it all, and we may never will.

But that’s okay because every advantage acquired brings us closer to the life we want.

Just being aware of this paradox puts you in a special club.

May knowing this increase your intellectual curiosity and eagerness to learn.

Have a wonderful and restful weekend!

The Most Expensive Way to Go Broke

Posted February 18, 2026

By Sean Ring

The Bears Gather

Posted February 17, 2026

By Sean Ring

Omar Khayyam: Poet, Rebel, Astronomer

Posted February 16, 2026

By Sean Ring

The Devil in Mexican Mining

Posted February 13, 2026

By Matt Badiali

Is Civil War on the Cards?

Posted February 12, 2026

By Jim Rickards