Posted August 22, 2025

By Jim Rickards

Rickards on Sovereign Wealth Funds

What Is a Sovereign Wealth Fund?

Before diving into the investment implications, it’s helpful to describe what an SWF is, how they exist today, and what a U.S. SWF would look like.

Countries that run trade surpluses by exporting more than they import will accumulate that surplus in their reserve position. It’s no different than an everyday American who earns more than he spends. The excess is invested in stocks, bonds, savings, or real estate, among other assets. Other sources of wealth for a country in addition to trade surpluses include investment income in the form of interest, dividends, capital gains, rents, and royalties. Those income flows are also added to the reserve position. A country works just like an individual – if you make more than you spend, you accumulate the excess as a reserve.

Where Did The Idea Come From?

Before World War I, countries almost always held their reserves in gold and silver. This was called the mercantilist system. The more gold and silver you had, the more powerful you were. Countries (or empires) that saw their gold and silver slipping away would take extreme measures to stop the outflow.

One famous example involved the so-called Opium Wars of the mid-19th century. At the time, the UK was buying far more from China than China was buying from them. Silver was flowing from the UK to China to settle the trade deficit. (Historically, China had a preference for silver over gold, although in recent decades China has been a major buyer of gold.) British officials needed to find a way to balance trade. They decided to get the Chinese hooked on opium, which they grew in British colonies in India.

Naturally, the Chinese rejected opium imports, but the Royal Navy attacked Hong Kong and forced China to open its ports. The result was widespread drug addiction in China for the next hundred years. At least the British got to solve their trade imbalance and keep their silver.

After World War I, the world moved to a hybrid reserve system that included hard currency foreign exchange in addition to gold. This was called the “gold exchange standard,” and it opened the door to central banks holding foreign sovereign bonds in their reserves.

The post-1944 Bretton Woods system was called a gold standard, but in reality, only the dollar was linked to gold, and all other currencies were linked to the dollar. Since the U.S. did not want an outflow of gold, it encouraged trading partners to use their surplus to buy U.S. Treasury securities.

By the time Nixon closed the gold window in 1971 (which allowed trading partners to exchange dollars for gold), the practice of holding reserves in U.S. Treasuries instead of gold was well established. That remains the case today with about 60% of all global reserves held in U.S. Treasury securities. The remainder is held in German, Italian, Japanese, and UK bonds and gold.

Central banks and finance ministries that managed reserve positions after Bretton Woods were extremely conservative. They emphasized safety and liquidity. In practice, this meant massive holdings of short-term U.S. Treasury bills, which could be rolled over continually and could easily be converted to cash if needed. This approach was amplified by the Asian-LTCM financial crisis of 1998. Central banks increased their reserve positions enormously on a “precautionary” basis as protection against a new financial crisis.

This precautionary saving has led to enormous reserve positions. China has $3.6 trillion in reserves (about 1/3 in Treasuries). Japan has $1.2 trillion, Switzerland has $953 billion, Russia has $620 billion, and India has $605 billion. Other large holders include Taiwan, Saudi Arabia, South Korea, and Brazil.

As reserve positions were growing, countries began asking themselves if there was a better way to invest for the benefit of their citizens. Some cash and liquidity are needed, but cash (or cash equivalents such as Treasury bills) generally have the lowest yields. Countries saw that equities, real estate, and corporate debt might all have higher returns.

This insight gave rise to the sovereign wealth fund. The idea was that some reserves would be kept in liquid, safe investments at central banks, and other reserves could be placed in a separate entity that would invest in riskier but higher-yielding assets.

How Many SWFs Are There?

SWFs began in 1953, but as late as 1999, there were only 20 SWFs in existence. Starting in 2006, there was an explosion in the formation of SWFs. Eleven SWFs were formed in that year alone. Twenty-two additional SWFs were formed between 2007 and 2012.

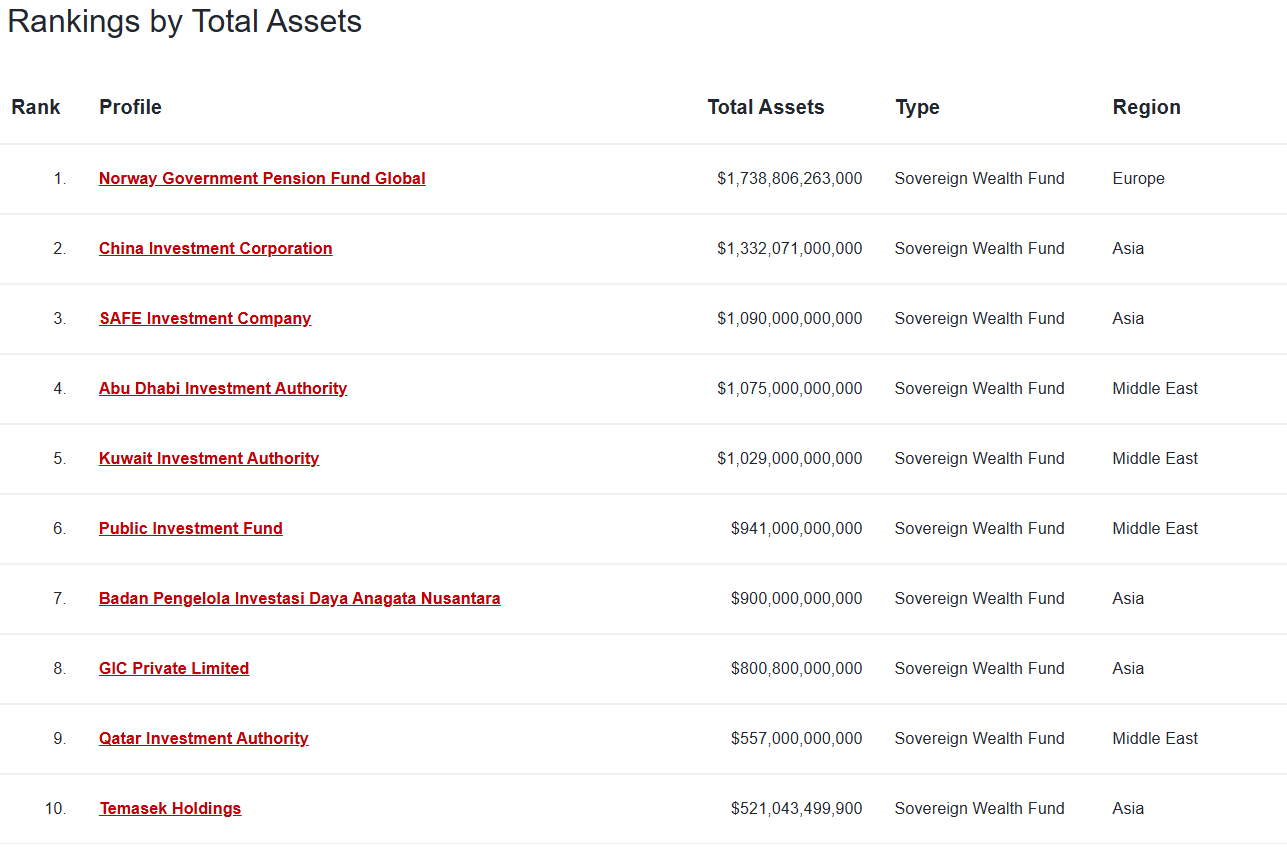

Today, there are a total of 99 SWFs on six continents. Total assets under management for all SWFs are over $9.1 trillion, with just 10 SWFs holding over 78% of those assets. The largest SWFs in the world are Norway ($1.7 trillion), China ($2.4 trillion in two entities), Abu Dhabi ($1.1 trillion), Kuwait ($1.0 trillion), Saudi Arabia ($925 billion), and Singapore ($800 billion).

The Top Ten largest sovereign wealth funds, managing

The Top Ten largest sovereign wealth funds, managing

over $9.6 trillion in combined assets:

The global asset allocation for all SWFs combined is: equities (30%), bonds (28%), Illiquid alternatives such as private equity and hedge funds (23%), liquid alternatives such as money market funds (4%), strategic investments (10%), and cash (5%). SWFs hold relatively little gold, which is more typically held by central banks and finance ministries. Over 57% of all SWF assets are funded by natural resources such as oil, natural gas, hydroelectric, strategic metals, and grain. The remainder is funded with other contributors to reserves such as manufactured goods, remittances, and investment income.

SWF managers can have an enormous impact on global asset prices based on their sheer size and the fact that managers tend to act in similar ways based on uniform risk models, even if there is no outright coordination. If SWF managers conclude that the AI boom is over, even a gradual diminution of their allocations to that sector can create enormous headwinds for AI stocks, if not an outright crash.

Can It Be Used As A Financial Weapon?

I’ve had first-hand experience meeting with major sovereign wealth funds. A few years ago, I met in Beijing with officials of the China Investment Corporation (CIC), one of the two major Chinese SWFs. (The other is the State Administration for Foreign Exchange, SAFE).

I presented their team with an opportunity to invest in a gold equity fund managed by a highly seasoned and well-respected gold investor. I noticed that one of the officials on the CIC side was silent and unsmiling with a brusque demeanor. He got up and left about halfway through the meeting without saying goodbye. It turns out he was a Communist Party “minder” whose sole purpose was to make sure we Americans were not spies and the Chinese were not overly friendly. I thought, “Welcome to Beijing.”

While my gold investor client was bona fide, I did do quite a lot of work for the U.S. intelligence community on SWFs at a time when we were concerned that they could be used for financial warfare, market manipulation, or acquisitions of U.S. target companies for the purpose of extracting valuable intellectual property or classified information. The line between legitimate SWFs and weaponized SWFs is not always clear.

What Do You Fund A SWF With?

Trump’s decision to launch a U.S. sovereign wealth fund raises several interesting questions.

Almost all SWFs are funded with trade surpluses. The U.S. has a trade deficit. How would a U.S. SWF be financed? One obvious path is for the U.S. Treasury to borrow money by issuing bonds and then contribute that money to the SWF. That works, but the debt aspect makes the SWF look more like a hedge fund using leverage. This path could also crowd out other Treasury debt issuance under the U.S. debt ceiling. Having Congress raise the debt ceiling to accommodate SWF finance could prove politically toxic.

A SWF could be funded with new sources of U.S. revenue, such as tariffs, even if the U.S. were still running a trade deficit. Tariffs could raise $10 billion or more in annual revenue based on current trade patterns. That revenue would make a good foundation for an SWF.

Another path is to contribute assets to the SWF that the U.S. already owns. These assets could include gold from Fort Knox, federal lands with oil and gas potential, and intellectual property that could be leased to third parties. But all of that monetization of federal assets can be done today under existing authorities without using a SWF. It’s not clear what an SWF contributes to that asset monetization.

Finally, Trump could contribute billions of dollars of cryptocurrencies that the U.S. has seized as a result of crypto-fraud, use of cryptos by criminal gangs, or cryptos acquired as penalties in legal proceedings.

Who Runs The Fund?

Another critical aspect of the SWF plan is the White House's choice for a fund manager. Will the job be awarded to large asset managers such as BlackRock, State Street, and JPMorgan, or will government officials manage the fund? If so, which ones? Most SWFs are conservatively managed even as they seek riskier assets. The U.S. SWF manager will be in a mighty position in global financial markets. A trusted fiduciary is the best approach for management but the temptation to award the job as a plum for political loyalty will be great.

The most important issue is whether the U.S. SWF will be managed strictly for high risk-adjusted returns or whether it will be weaponized to pursue geopolitical goals through financial manipulation. The former would suggest a seasoned fiduciary should be in charge. The latter approach would call for diplomatic and intelligence inputs alongside financial expertise. That choice will have a large impact on what investment decisions the U.S. SWF makes.

Right now, we have more questions than answers. But knowing the right questions leaves us in a good position to interpret announcements and stay ahead of the curve when it comes to the impact on markets that a U.S. SWF will have. That impact will affect your personal investment portfolio. We’ll be following developments and keeping you informed every step of the way.

The Fed's Cook is Goosed

Posted August 26, 2025

By Sean Ring

Trump’s Tariff Timebomb

Posted August 21, 2025

By Sean Ring

How the Gold Price Moves

Posted August 20, 2025

By Sean Ring

Fuera MAS!

Posted August 19, 2025

By Sean Ring

Alaska: Good Trump, Good Putin

Posted August 18, 2025

By Sean Ring