Posted March 21, 2024

By Sean Ring

Prez Pressuring Powell?

When Jay Powell looks in the mirror, he wants to see Paul Volcker. But by the end of his run as Fed Chairman, he may see Arthur Burns.

You may not remember Arthur Burns at all. But just over 50 years ago, Burns was the Chairman of the Federal Reserve. Richard Nixon nominated him for the job more because Burns was a conservative rather than an eminent economist.

And it was a stroke of genius, that move. Because Burns lowered interest rates in 1972 to help get Nixon re-elected.

In a fascinating paper titled “How Richard Nixon Pressured Arthur Burns: Evidence from the Nixon Tapes” by Burton A. Abrams, the author makes some choice observations.

Here’s the first one that caught my eye:

In Nixon’s 1962 (p. 309-310) book, Six Crises, he recounts that Arthur Burns called on him in March 1960 to warn him that the economy was likely to dip before the November election. Nixon writes that Burns “urged strongly that everything possible be done to avert this development. He urgently recommended that two steps be taken immediately: by loosening up on credit and, where justifiable, by increasing spending for national security.” But when then–Vice President Nixon took this recommendation to the Eisenhower Cabinet, “there was strong sentiment against using the spending and credit powers of the Federal Government to affect the economy, unless and until conditions indicated a major recession in prospect.” Nixon sums up: “Unfortunately Arthur Burns turned out to be a good prophet.”

This episode stuck with Nixon. First, Nixon blamed a modest rise in the unemployment rate as one of the reasons he lost the presidential election to John F. Kennedy in 1960. Second, the messenger was indeed a good prophet.

The second statement demonstrates Nixon’s power over Burns:

Richard Nixon demanded and Arthur Burns supplied an expansionary monetary policy and a growing economy in the run-up to the 1972 election. … M1 growth increased in each of the three years, starting at approximately 4.5 percent growth in 1970 and ending at slightly over 7.5 percent annualized growth over the first half of 1972. M2 growth expanded even faster. Real growth in the economy was accelerating, too. In 1972, real GDP grew 7.7 percent and certainly helped Nixon in the election.

Abrams continues:

Thus, a monetary stimulus helped to boost the economy in time for the 1972 election, helping to deliver Nixon’s landslide victory. However, the excessive aggregate demand stimulation prior to the election created serious problems for the economy that took nearly a decade to resolve.

And how about this telephone conversation on December 10, 1971:

With fewer than eleven months until the election and four days until the next meeting of the Federal Open Market Committee, Burns and Nixon have a private telephone conversation. Burns states that “I wanted you to know that we lowered the discount rate...got it down to 4.5 percent.” “Good, good, good,” replies Nixon. Burns indicates that the announcement of the discount rate reduction would be accompanied by the usual statement that it was done in order to bring the rate into line with market conditions, but with an added statement that it was done to “also further economic expansion.” Burns exclaims that he also lowered the rate to “put them [the Federal Open Market Committee] on notice that through this action that I want more aggressive steps taken by that committee on next Tuesday.” “Great. Great,” replies Nixon. “You can lead ‘em. You can lead ‘em. You always have, now. Just kick ‘em in the rump a little.” Burns urges the president to do something about the Pay Board and the Cost of Living Council, who, in his opinion, are “holding back recovery” by squeezing businesses by restraining price increases relative to wage increases. Burns adds adamantly: “Time is getting short. We want to get this economy going.”

Note: The discount rate is the interest rate the Federal Reserve charges commercial banks and other financial institutions for short-term loans. The discount rate is applied at the Fed's lending facility, which is called the discount window. The discount rate played a more important role in monetary policy in 1971 than it did in recent times and usually was set below the federal funds rate.

I write all this because I want you to know the Federal Reserve’s “independence” is, in the words of our Muddlehead-in-Chief, a load of malarkey.

Powell’s Press Conference

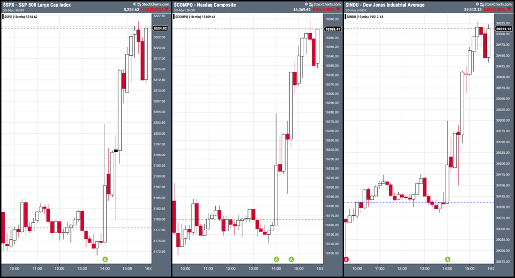

Below is yesterday’s market, split out by 10-minute candlesticks. Do you notice anything at 2 p.m. (14:00)?

The SPX, Nazzie, and Dow roofed it. Bitcoin (not shown) jumped over $7,000 to nearly $68,000. Why?

It's because Jay Powell isn’t taking away the punch bowl. In fact, he’s loading us up for more!

The FOMC statement opened up like this:

Recent indicators suggest that economic activity has been expanding at a solid pace. Job gains have remained strong, and the unemployment rate has remained low. Inflation has eased over the past year but remains elevated.

If that’s the case, why are rate cuts even on the table?

NikiLeaks got it right in today’s Wall Street Journal:

Higher housing prices and stock-market gains are boosting wealth and thus supporting consumption, especially in high-income households. The price of bitcoin has recently surged to records, a sign of exuberant risk-taking.

With GDP growth at 3.2%, inflation at 3.1%, and unemployment at 3.9%, Jay Powell is still discussing three rate cuts this year.

Incredible?

Not if you remember Burns and Nixon.

NikiLeaks continued:

Democrats are nervous that higher rates are sapping consumer sentiment and risking a slowdown ahead of November’s elections. This week, a handful of the most liberal lawmakers called on Powell to cut rates.

“We read these letters with respect,” Powell said. “But at the end of the day…we have to make our judgments.”

It’s not a question of “If,” but “When?” when it comes to rate cuts, regardless of what the data reads.

Wrap Up

Everyone wants something for free, especially money. That’s why no one wants to pay interest.

But if we’re going to have a functioning economy, we need appropriate, market-determined interest rates. The old men in the Fed are too susceptible to political pressure, especially when they don’t want to work for Orange Man.

Cutting rates here will feel really good.

But leaving rates too low for too long will lead to problems that will take a decade to fix.

Trump’s Long, Short War

Posted March 13, 2026

By Byron King

The Everything Problem

Posted March 12, 2026

By Sean Ring

Ghosted at Gunpoint

Posted March 11, 2026

By Sean Ring

The Best of All Possible Worlds

Posted March 10, 2026

By Sean Ring

Donald's Domestic Destruction

Posted March 09, 2026

By Sean Ring