Posted October 08, 2025

By Byron King

Let There Be Light!

In 1922, two young men graduated from Tufts College in Boston. America was recovering from a post-World War I recession, and they couldn't find jobs, so they started their own business. They set up a company to make a new-fangled device called a refrigerator.

Today, that company is valued at over $200 billion, but it’s long past making refrigerators. In fact, it’s a giant in the world of defense technology and critical to the defense of the U.S. and many of its allies. Here’s how it happened…

And of course, I’ll explain how you can benefit from owning shares in this firm. While we’re at it, the company’s fascinating history helps tell the tale. So, let’s dig in.

First, the Refrigerators!

Back in the 1920s, people kept food cold with something called an “icebox,” literally an insulated wooden box that held blocks of ice. Considering the logistics and expense of making or storing ice in those days, keeping things cold was a luxury reserved for the upper classes.

However, in the 1920s, America also began to electrify. People wanted indoor lighting, and electric bulbs were better than oil or gas lamps. As the Roaring Twenties unfolded, more and more homes and businesses wired into utility companies for power.

With electricity use expanding, people began to devise other ways to harness that power. One idea was to use electricity not just for light bulbs, but also to run a compressor. That is, a compressor could cool things down and thus keep food cold. Hence came the idea of an electric-powered refrigerator to eliminate that insulated box full of ice.

Of course, in 1922 if you wanted to build refrigerators, you had to come up with your own parts. It’s not like you could outsource requirements to, say, China. So, the two Tufts grads quickly figured out that they had to manufacture mechanical and electrical components.

One item that the two men developed was a device to convert alternating current into direct current, to run an electric motor. They constructed a helium-filled electron tube, which we today call a transformer-rectifier. They installed it in an early model of their refrigerator, where it worked well, as did the refrigeration idea. And then something fateful occurred.

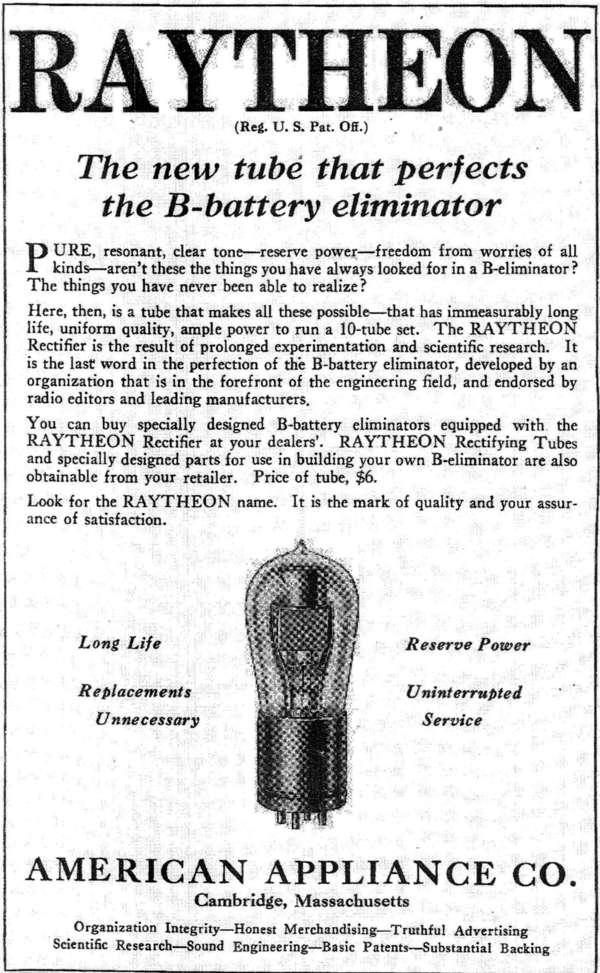

Word spread about this new rectifier-thingy. The device gained popularity among radio enthusiasts, a time when radios relied on crystals and direct current. So, this novel tube, originally developed for refrigerators, allowed radio operators to use everyday household alternating electric current, eliminating the need for expensive, short-lived batteries.

Faced with growing demand for their innovative "battery eliminator" rectifiers, the two founders changed their company's business model. Instead of building refrigerators, they began to assemble electronic devices. And they decided that they needed a new name for their company.

1920s ad for Raytheon power-rectifier. Courtesy radiomuseum.org.

1920s ad for Raytheon power-rectifier. Courtesy radiomuseum.org.

Light from the Gods

When powered up, the helium-filled glass tubes emitted a soft glow. The two company founders were savvy enough to realize that this phenomenon might help them create a memorable brand. Plus, they figured that it might help to use Greek-sounding words because that sort of thing conveys an aura of intelligence and sophistication. So they used the Greek words for “light from the gods,” which sounds like the word “Raytheon.” And thus was born the Raytheon company, now called RTX Corp. (RTX).

I'll skip ahead and say that, today, this former refrigerator maker is now among the world's largest defense and aerospace contractors, specializing in high-end electronics, missiles, jet engines, and much more. Headquartered in Waltham, Mass., just outside Boston, Raytheon/RTX is a key supplier of critical defense-related products, which I'll describe below.

RTX shares trade in the range of $160, and the price-earnings ratio is over 35. The dividend is 1.7% and growing over time. The numbers are pricey in some respects, but keep in mind that RTX is a high-tech company with a wide-open future (see below), and I don’t mean gimmicky vaporware like many other names that trade at lofty metrics.

RTX holds a significant position in the fast-growing market for U.S. defense and commercial aerospace needs, as well as for innumerable allied and friendly nations that buy and utilize the company’s many wares. Indeed, the current RTX sales backlog is in the range of $125 billion commercial, and not quite $100 billion defense. This includes missiles, defense electronics, commercial aerospace, jet engines under the Pratt & Whitney name, and much else.

In essence, Raytheon/RTX has a rock-solid book of business, and it’s likely (especially when you consider the perilous state of the world) that its reach will grow steadily, if not rapidly. But what is it about RTX that radiates such light from the gods, so to speak? Well, let’s revisit that original transformer-rectifier, developed in the 1920s.

The Sharpest of Cutting Edges

Raytheon/RTX has long been out in front of technology and innovation, as the story of refrigerators to radios demonstrates. And today, it’s no stretch to say that innovation and success are ingrained in the very DNA of the company.

In the 1920s, Raytheon quickly became the leading manufacturer of electron tubes and switches. It competed successfully against established names like General Electric, Westinghouse, and RCA. And despite this big-name competition, Raytheon's tubes and switches became critical, go-to components for the then-booming radio industry, as well as electric-oriented industrial sectors like power generation and distribution.

In 1933, as the Great Depression unfolded, Raytheon acquired Acme-Delta Company, another leading producer of power equipment, transformers, and electronic auto parts, and this deal paid off handsomely in just the next few years. That is, in the 1930s, the U.S. government built numerous hydropower dams across the country, such as on the Colorado and Columbia Rivers, and through the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA). The idea was to "electrify" the country, and that created a pressing need for exactly what Raytheon made and sold. By the late 1930s, Raytheon had established a strong position in the nation's electricity, electronics, and radio transmission sectors.

Then came World War II.

The Radar Trade

The war in Europe began in September 1939 when Germany (and later the Soviet Union) invaded Poland. By mid-1940, France fell, and Great Britain stood alone in the battle against Nazi Germany. Despite the European carnage, U.S. public opinion opposed entering the war. Still, U.S. companies sold supplies and equipment to the British.

In mid-1940, British representatives, on a secret mission to Washington, presented the U.S. government with an entirely new form of technology. They offered to share the secrets of a device called a "magnetron," which generates microwaves. To make a long story short, magnetrons form the basis for what we call radar -- "radio detection and ranging."

U.S. government scientists and military leaders examined the British devices and were astonished. They summoned several of the brightest minds from the physics department at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and asked for advice, which was to acquire this radar technology and develop it as quickly as possible.

Under tight security, the U.S. government searched for organizations capable of mass-producing magnetrons and installing them into radar systems for ground stations, ships, and even for aircraft. To no surprise, the MIT profs recommended Raytheon as a manufacturer.

By late 1940, Raytheon had a secret government contract to produce magnetrons and build radars. By 1942, Raytheon's first "seagoing" (SG) search radars were onboard Navy vessels. As the war progressed, Raytheon SG radars became standard technology for providing vital situational awareness to commanders during all of the major battles in the Pacific theater.

Meanwhile, in the Atlantic Theater, both airborne and surface versions of Raytheon radars played a critical role in detecting German submarines and ultimately winning the Battle of the Atlantic. When the war ended in 1945, Raytheon had produced about 80% of all magnetrons used in the conflict.

As an aside, Raytheon's work with magnetrons revealed the potential of microwave energy to cook food. So, in 1945, a Raytheon engineer came up with a device called a "microwave oven." In 1947, Raytheon demonstrated its now-iconic "Radarange" for commercial use.

The Missile Age

Microwave ovens were an interesting idea, but Raytheon kept its post-war business focus on things it understood, especially radar. This included research into guidance systems for aircraft and then for missiles. To make another long story short, in the years following World War II, Raytheon essentially invented the guided missile.

In 1950, the Raytheon "Lark" missile became the first guided weapon to destroy a target aircraft in flight. Then, during the Korean War, Raytheon received extensive contracts for more and more weapons across a wide range of capabilities.

Raytheon missiles on display at the Paris Air Show. Courtesy RTX Corp.

Raytheon missiles on display at the Paris Air Show. Courtesy RTX Corp.

Since the Korean War days, and over the past 75 years and more, Raytheon's efforts have covered quite a bit of the military waterfront. Indeed, people write books on things like this, but the short version is that Raytheon received military contracts that turned into a large family of air-to-air missiles: the short-range "Sidewinder," as well as its longer-range "Sparrow" counterpart, and the very long-range "Phoenix" system, plus current and evolving versions of the “AMRAAM” system (advanced medium range air-to-air missile).

On the ground, Raytheon developed the "Hawk" air defense missile, which later evolved into the anti-air "Patriot" system. Plus other weapons with names like “Coyote,” currently in use to shoot down drones in various theaters of conflict.

For ships, Raytheon developed and currently supplies a variety of surface-to-air missiles, the best-known being the "Standard" series, a keystone of U.S. anti-ballistic missile capabilities. All from the former refrigerator-maker in Boston.

A Growth Story

As is the case with most large companies, over time, Raytheon/RTX made numerous acquisitions. Things came and things went away, depending on circumstances, and again, there's much history.

Since the 1990s, Raytheon/RTX has collaborated with Israel to develop the "Iron Dome" system, which now defends the country against incoming rounds. And looking ahead, expect RTX to be a key player in President Trump’s “Golden Dome” defense system for the U.S. homeland.

Also, looking back to the 1990s, as the Cold War unwound, many former U.S. defense companies exited the field or went out of business. And in this environment, Raytheon/RTX bought many outstanding firms and/or assets at a relative bargain. These include the former electronic warfare leader, E-Systems, as well as the defense units of Texas Instruments and Hughes Aircraft.

Along the way, Raytheon/RTX acquired the underwater torpedo business of Honeywell, Westinghouse, and Gould. And Raytheon is now a key supplier to the U.S. Navy and other foreign governments of lightweight Mk-54 torpedoes, and the heavyweight Mk-48 submarine-launched weapon.

Also, Raytheon/RTX acquired Collins Aerospace, a maker of electronic systems, and it combined with United Technologies to take over the Pratt & Whitney jet engine business.

In defense alone, Raytheon/RTX's business units produce air-, sea-, and land-launched missiles, aircraft radar systems, weapon sighting and targeting systems, communication and battle-management systems, and satellite components.

For example, you'll find Raytheon/RTX radars in the front end of the F-15 Eagle, F-16 Fighting Falcon, F/A-18 Hornet, F-22 Raptor, and the B-2 Spirit bomber. Additionally, Raytheon/RTX radars are installed in a wide range of drone aircraft.

Other Raytheon/RTX programs include the Space Tracking and Surveillance System (STSS), which is part of the Ballistic Missile Defense Organization (BMDO). Combined with other systems, Raytheon/RTX products have successfully destroyed missiles at many phases of their flight path and indeed have shown a capability to destroy satellites in orbit.

Meanwhile, Raytheon/RTX is a leader in laser systems, having pioneered the first working model of such devices in 1959. Today, highly advanced Raytheon laser components are moving into the field and fleet for U.S. military operational testing and evaluation.

Not to overload you, but Raytheon/RTX also boasts a strong "homeland security" business segment. This includes systems for detecting contraband, particularly radioactive materials, at border crossings.

Miniaturized RTX chips for Patriot missile, next to a dime. Raytheon/RTX Photo.

Miniaturized RTX chips for Patriot missile, next to a dime. Raytheon/RTX Photo.

And Raytheon/RTX is a leader in developing specialized, miniature semiconductor materials for the electronics industry, including gallium arsenide (GaAs) and gallium nitride (GaN) components for next-generation detectors, radars, and optical systems.

Over the past century, many great old companies have come and gone. But a few firms actually had what it takes to adapt and survive through changing times. Among the best of this survivor group is Raytheon/RTX, with a rich history, solid current book, and bright future. Indeed, the company’s future could be said to be illuminated by that so-called “light from the gods.”

I’ll end here and note that Raytheon/RTX is not in the official newsletter portfolio, but I do follow developments with the company. As noted, the company has a solid future and limited downside considering current government procurement trends for missiles and other electronic systems. Still, if you buy shares, be sure to watch the charts, wait for down days in the market, always use limit orders, and never chase momentum.

That’s all for now. Thank you for subscribing and reading.

The Devil in Mexican Mining

Posted February 13, 2026

By Matt Badiali

Is Civil War on the Cards?

Posted February 12, 2026

By Jim Rickards

Isn’t Mining Dangerous Enough?

Posted February 11, 2026

By Sean Ring

A Tale of Two Italys

Posted February 10, 2026

By Sean Ring

Take The Money and Rotate

Posted February 09, 2026

By Sean Ring