Posted February 27, 2024

By Sean Ring

King: Fracking 101

Today, my good friend and frequent Rude contributor Byron King is taking us on a field trip.

We’re heading to Colorado, where Byron will take us through his Fracking 101 course.

Enjoy and I’ll see you tomorrow!

A Field Trip to Colorado: Fracking 101

Nobody can squeeze 6,000 feet down a drill pipe to look at an oil-bearing rock formation. Plus, it’s dark at the bottom of an oil well and hard to see anything.

A while back, though, I had a chance to do the next best thing to being there. In fact, I found myself up close and personal next to one of the hottest, most prolific “tight oil” shale plays in the country.

I placed my hands directly onto oil-bearing strata. I could see and smell the petroleum. Indeed, I held the gooey goop in my fingers:

Gooey, oil-rich shale in your editor’s hand. BWK photo.

If you’re curious, it smells a lot like money — both money going down the hole and money coming back out. Problem and opportunity, in other words.

There’s plenty to discuss here. Because what I was doing out in the field was not nearly as simple as just picking up rocks off the ground.

In fact, I was visiting nothing less than a combination of geological marvel and industrial-technological miracle.

Of course, there’s huge money tied up in all of this too, and I mean trillions of dollars. No typo: trillions.

Let’s dig in…

Today, we’ll take a field trip to the high plains of Colorado, northwest of Denver. The adventure was pre-Covid, when I visited a major drilling and oil-producing operation run by the former Noble Energy Corp., which was acquired in July 2020 by Chevron (CVX: NYSE).

Here’s how it unfolded. Noble (and for clarity, I’ll call it “Noble” even though it’s now Chevron) sponsored a field trip to one of its major operations. I paid my own way to Denver and paid for the hotel and incidentals. Noble supplied a bus and several outstanding geologists to narrate the tour.

Over the course of a long day, we went to several geological sites and kicked rocks. We also visited drilling and production sites to see development and oil handling operations.

Broadly, the purpose of all this was to learn more about fracking, the process of drilling a well, pressurizing the hole and fracturing (“fracking”) the rock to release oil and gas.

Along these lines, it’s fair to say that most people have never been close to a drilling rig or oil operation, particularly politicians and policymakers (and it shows).

Most of what people think they know about oil operations comes from reading a book, from news articles or watching television or such.

It’s also fair to say that most people don’t know much or understand even the basics of fracking. So the idea behind my field trip (and of this discussion today) is to take a look at real oil operations and learn a few things. After that, you can draw your own conclusions.

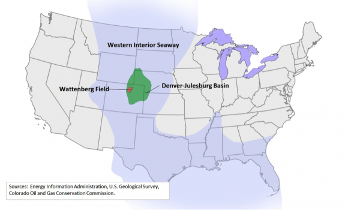

Begin with a map that shows a geological feature called the Denver-Julesburg Basin (DJB), which underlies eastern Colorado, western Nebraska, etc. And there’s a site in the DJB called the Wattenberg Field, a major oil production area.

The key to Noble’s project was control over vast acreage in this DJB region. In particular, there are prime locales nicknamed “sweet spots,” mostly within a rock formation called the Niobrara Shale, which underlies much of the Great Plains of the U.S. and Canada.

This Niobrara feature is a hydrocarbon-rich rock formation laid down long ago in Cretaceous time, 99 million to 65 million years ago. It formed in what geologists call the Western Interior Seaway; and here’s another map of the ancient dimensions, to give you an idea.

Long ago, the U.S. and Canada Great Plains were underwater.

Long ago, the U.S. and Canada Great Plains were underwater.

Courtesy Niobrara News.

http://www.niobraranews.net/niobrara-formation-genesis/

The good news for geologists is that Niobrara outcrops at the surface, adjacent to the Front Range of the Rocky Mountains, just north of Denver. And that’s where our Noble geologist-guides began the field trip, at a limestone quarry operated by Cemex (CX: NYSE), the large, international cement-maker.

In other words, the point of visiting the Cemex quarry was to see rocks exposed at the surface, particularly the entire thickness of Niobrara. This alone helps to understand why this oil play is such a remarkable energy asset.

Basically, when Niobrara was laid down long ago, the ocean mud and ooze were filled with ancient sea life from fish in the water to microbes in the muck. When they died, they were buried under layers of fine sediment, much of it clay which is why we have shale.

Over the past 65 million years, the remains of these buried critters chemically transformed into oil and gas within the rock, although one can still find a few fossils here and there.

Fossil clam shell in Niobrara Shale. BWK photo.

Meanwhile, just beneath the Niobrara is an older, dense rock formation called the Fort Hayes Limestone. That’s what Cemex quarries and grinds up for lime, with which to make cement.

The geological layout is that, pre-Niobrara, the Fort Hays Limestone subsided and became the foundation, so to speak, for subsequent shale deposition. One thing follows another, right?

Here’s a photo of several members of our field trip standing atop Fort Hayes, which plunges downward rather steeply toward the east, away from the mountain range.

Standing on plunging limestone; Niobrara Shale above. BWK photo.

In the photo below, as you look out over the quarry, you’ll see literally the entire thickness of Niobrara, nearly 400 feet at this locale. Cemex removes all this shale just to get to the underlying limestone, which says something about the value of limestone used for cement-making.

And as this photo shows, there are massive, energy-intensive, earth-shifting operations involved in all of this.

Cemex blasts and removes Niobrara shale to get to the underlying limestone. BWK photo.

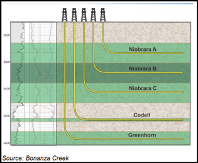

More of interest to oil-finders, as opposed to cement-makers, is that the Cemex quarry exposes four key layers of Niobrara, labeled A, B, C, and D. The Niobrara formation also has a couple of other lower zones, called Codell and Greenhorn.

Way over east — about 30 miles or so, near Greely, Colo. — these rocks are buried 6,000 feet deep under many younger layers of rock. And this rock is what drill bits penetrate to make oil and gas wells. Here’s a schematic to help you visualize things.

The idea is to drill directional wells into Niobrara Shale; and then frack it for oil.

Source: Naturalgasintel.

That’s the basic geology. You have a hydrocarbon-rich shale atop a sturdy limestone bed underneath. It’s all uplifted, in the sense that the surface is well over 4,000 feet in elevation. But in the DJB the underlying rocks are not heavily folded, faulted, or fractured by natural processes.

Now let’s move on to what the Noble reps explained about their wells when we visited actual drilling and production operations, east of that Cemex quarry and out in the Greely area.

A typical well drilled into the Niobrara goes down about 6,000 feet from the surface and then about 5,000 feet outwards or “laterally;” although some wells are as much as 10,000 feet lateral. This involves flexible drill pipes and very sophisticated drill bits guided by astonishing navigational tech.

The idea is to drill as much hole as possible, through the oil-rich shale. This maximizes the surface area available to drain oil from the otherwise impermeable rock. Geologists and engineers call it “maximizing the pay zone.”

This kind of directional drilling is a remarkable technical achievement in general. The ideas (and patents and trade secrets) took several decades to mature in the 1980s, 90s and 2000s. Plus, each oil-bearing region is different, so people who work in an area tend to develop in-house approaches.

Over time — basically from about 2012 to 2019 — Noble’s engineering talent and the company’s drilling contractors became astonishingly proficient at grinding wells through the rocks far beneath that Colorado prairie.

One particular Noble well set a speed record, requiring all of five days “from spud to spud.” That means that Noble drilled one well in five days, totaling about 11,000 feet of hole. And then the driller reset the rig and began preparing to drill the next well in the series. Frankly, that’s really impressive.

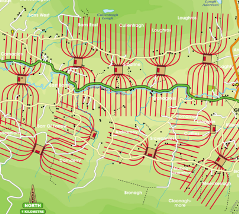

Noble’s approach has been to drill numerous wells from a single “pad,” meaning a relatively small area, usually under about 4 acres. There, the company stages the rig, equipment, machinery, supplies, and the like. The wells go outwards laterally, so that if you look down it’s like seeing spokes on a wheel or the teeth on a comb.

Top-down view of drilling patterns in a fracking operation.

After the wells are drilled, the rig moves on to other jobs, while topside production equipment has a minor footprint, as you can see in these shots here:

Noble wells and production pads in DJB area.

In the mid-2000s, the DJB area became dotted with pads and wells. The typical Noble pad supports 16 wells. Each cost about $4 million to drill, for a total of about $64 million per full pad. Of course, numbers vary from site to site; these are average figures.

Early on, a run-of-the-drill Niobrara well flows at rates of 400 to 700 barrels per day. One Noble geologist stated, though, “We’re interested in maximizing long-term oil recovery; not in making splashy press releases about early flow-rates.”

Per Noble, each well has an anticipated life of up to 30 years, with estimated ultimate recovery of about 350,000 barrels of oil to include associated gas and natural gas liquids (NGLs).

So with 16 wells per pad, at 350,000 barrels each, we’re looking at about 5.6 million barrels per pad over the life of the operation. And this doesn’t include the possibility of “re-entering” a well in the future for new drilling, well-expansions or “re-fracking” an old well. That’ll bump up the numbers.

But let’s stick with that 5.6-million-barrel number.

About 70% of the oil comes out in the first six years, or just over 3.9 million barrels.

And let’s say that the price per barrel is about $50, which is on the low side just now.

The math totals to $195 million of cash flow per pad over six years. It more than pays down the initial $64 million capital cost to build out the operation. Although ongoing production maintenance and transportation also must be factored in.

The good news for Noble has been that the geology and well costs paid for profitable operations. Such was not the case with many other fracking plays across the U.S., though; each oil field and region has its own tale to tell.

But for Noble (now Chevron, as I noted above), that Niobrara rock still delivers immense volumes of oil and gas, much of it up front in the life-cycle and with strong economics. At $50 or more for oil, these DJB fracking plays made money for Noble and still do for Chevron.

Still, as we’ve discussed in other articles, U.S. fracking may well be just a moment in time for the nation’s energy needs. That is, much fracking was funded with low-interest, “cheap” money all through the 2010s, courtesy of U.S. monetary policy and a long list of circumstances that are unique to the American oil patch.

And even the best U.S. operations face severe headwinds from anti-fracking and anti-carbon policymakers from the local end to the state capitol in Denver and to far off Washington D.C. It’s an uphill climb for even the best of operations.

Of course, the broader question remains of how the U.S. will remain an energized society. The U.S. uses about 20 million barrels of oil per day. It has to come from somewhere.

Looking ahead, how will we keep the wheels rolling and the lights on?

From the standpoint of history, that trip to the Cemex quarry and Noble well pads represented about 150 years of human ingenuity and effort to come up with all the ideas and technology that makes this work.

And clearly, we have people in power right now who want to toss it all out, starting yesterday, and which will make for a rough time tomorrow.

We’ll see how this unfolds. It’s all a story yet to be written.

I’ll end with one last interesting point.

Remember that Fort Hayes Limestone I mentioned earlier, which Cemex quarries? It turns out that quite a bit of it goes back down into the Niobrara — and I mean literally.

That is, Cemex is a major cement supplier to well-completion businesses that serve the oil industry across Colorado. Limestone goes from quarry to kiln to cement, which the likes of Halliburton (HAL: NYSE) then pumps down into the ground to secure the steel pipe that makes a well.

It’s kind of funny how geology works in real life. And how geology makes the rest of life possible as well.

And on that note, I rest my case.

That’s all for now… Thank you for subscribing and reading.