Posted February 13, 2025

By Sean Ring

If Germany’s Economy is Dead, Why is the DAX at All-Time Highs?

I’m grateful for colleagues like the Five’s Dave Gonigam on days like these. I know a lot is happening, but sometimes I wake up with a head emptier than Kamala Harris. But while I was in Poland, Dave emailed me with an article idea: “How can Germany be deindustrializing while the DAX 40 is at an all-time high? Are there any lessons for Americans?” Thank you, Dave!

Now, those are two fundamental questions that deserve to be answered.

Let’s get right into it.

German Deindustrialization

German deindustrialization isn’t a myth. The German economy is imploding because it depended on cheap Russian energy to keep the lights on and make a profit. The Ukraine war and Nordstream sabotage have thrown that out the window.

Credit: Capital Economics

Credit: Capital Economics

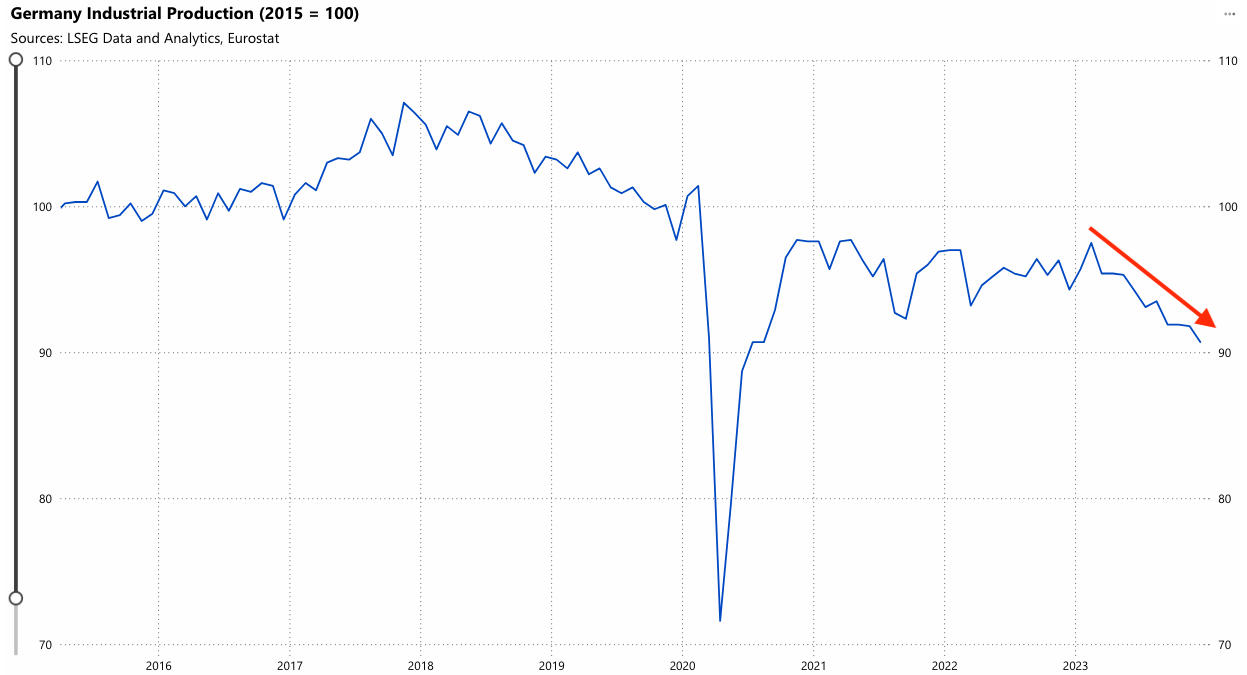

The above chart shows German industrial production. It’s been rotten and falling off a cliff since 2023. It’s nearly 10% worse since 2015, and there’s no sign of a recovery. (If the USG and Russia cut a deal soon and the US allows Germany to import Russian gas, we may have a different story soon.)

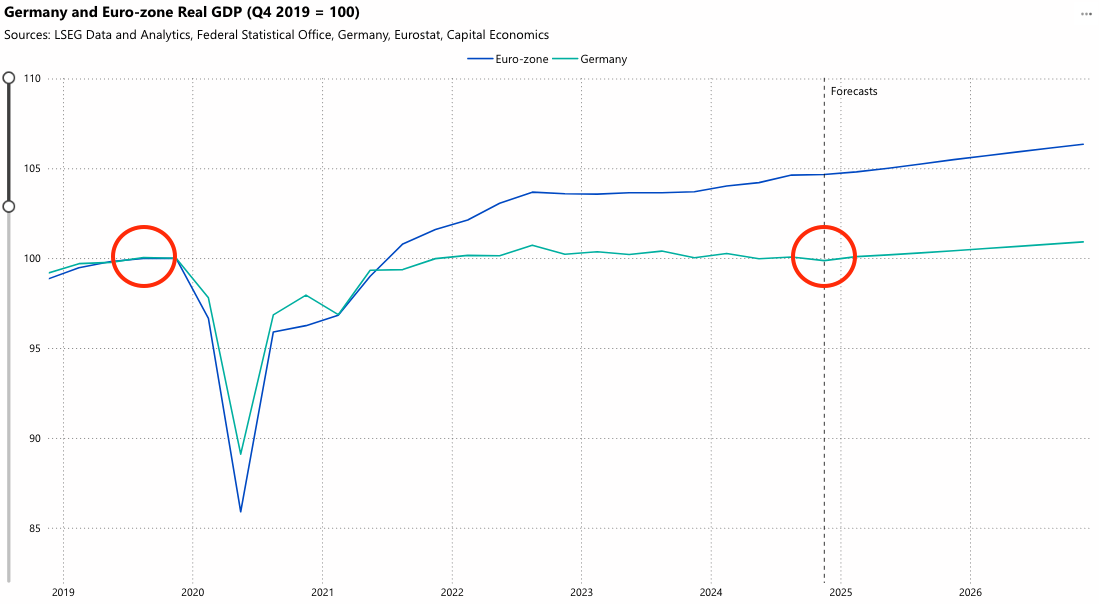

As for German GDP, it hasn’t grown at all since 2019.

Credit: Capital Economics

Credit: Capital Economics

So how is it possible that the German stock market, as represented by its DAX index, is doing so well?

The DAX 40

Well, this is one lusty chart if you ask me:

It’s perfectly sensible to ask the question: how on earth is the German stock market looking so good when the German economy looks like an 18-car pile-up?

My first thought was that currency depreciation brought this on. When you have a central bank (the European Central Bank, or ECB) whose sole task is to destroy your currency, your stock market will “gain” in value. If you think the Fed is feckless, you won’t believe how gobsmackingly inept Christine Lagarde and her toadies are. Buying a single German share will take more currency (euros, in this case). So, the stock isn’t increasing in value so much as what you use to buy the shares - the euro - is decreasing.

That’s a valid answer, but not the only reason this is happening.

Another reason is that the DAX isn’t the German economy. It’s heavily weighted toward multinational corporations that generate significant revenues outside Germany. Companies like SAP, Siemens, and Linde have global operations, so they benefit from strong performances in the U.S., Asia, and other markets. German small and mid-sized manufacturers (Mittelstand) are more exposed to domestic economic struggles, but aren’t in the DAX.

This also reinforces the first point about the euro's weakness in helping these companies. Once converted into a weaker euro, a strong USD flatters a company’s financials.

Another reason is that the DAX has fewer industry stocks and more tech and pharma stocks. While manufacturing and heavy industry are struggling, DAX firms in technology, healthcare, and financial services are booming. SAP, Germany’s largest company by market cap, is a tech firm that benefits from AI, cloud computing, and software demand. Industrial downturns affect healthcare and chemicals (e.g., Merck, Bayer, and Qiagen) less.

We must also remember the stock market doesn’t equal economic reality today. Equities are priced on future earnings expectations, not the present state of the economy. Investors expect further rate cuts from Lagarde’s ECB in 2025, boosting stock valuations by reducing the discount rate on future earnings.

Of course, momentum causes ETFs and index funds to buy DAX stocks automatically, supporting prices. Large companies' share buybacks also apply upward pressure.

If deindustrialization accelerates, it may eventually hurt long-term earnings for some DAX firms. But for now, global tailwinds and liquidity are keeping German equities strong.

Haven’t we heard this story before?

Charlie Munger and the Easiest Money Berkshire Ever Made

In the autumn of 2020, when the world was still scrambling to understand the long-term consequences of the COVID-19 scamdemic, Warren Buffett sat in Omaha, flipping through financial reports as usual. Charlie Munger was on the other end of the phone, but Buffett barely needed his input.

Japan was the world’s third-largest economy, but the ghosts of the 1989 crash still haunted its stock market. Foreign investors had dismissed it for decades as a land of stagnation, buried under debt, deflation, and bad demographics. But Buffett knew better—real value was hiding in plain sight.

The five Japanese trading houses—Mitsubishi, Mitsui, Itochu, Sumitomo, and Marubeni—were sprawling conglomerates, with their fingers in every pie from energy to agriculture to consumer goods. Investors dismissed them as ancient relics, their stock prices trading at absurdly low earnings multiples. Even better, they paid dividends north of 5% and were buying back their own shares.

More importantly, he had an ace—the yen was weakening. The Bank of Japan, terrified of another recession, was printing money like Weimar Germany. A falling yen made these firms even more competitive on the global stage, boosting their profits in local currency terms. And with inflation finally waking up, their commodity-driven businesses were about to become more valuable.

Buffett moved. Quietly and methodically, Berkshire Hathaway built its stake, starting with a $6 billion investment. No one noticed at first, but when the news broke, Japan’s financial media went into a frenzy. The Oracle of Omaha had made his biggest-ever bet on the country.

Buffett played it cool, telling the financial media he planned to hold these stocks for at least a decade. But he knew something the market didn't quite grasp: these companies weren’t just cheap—they were structurally mispriced.

Over the next three years, the yen fell even further, commodities rallied, and the trading houses boomed. Their stocks soared 100%, 200%, and even 300%, all while Berkshire collected dividends. Foreign investors, who had ignored Japan for years, suddenly woke up and rushed in, bidding up prices even further.

Berkshire made over $8 billion on the trade, but that number isn’t confirmed. It may be much more.

Charlie Munger described this investment as "like having God just opening a chest and just pouring money into it."

Is this what’s happening with Germany?

“Same, Same. But Different.”

There are similarities between what’s going on in Germany and what Berkshire did with those Japanese stocks. However, it’s not a repeat, but a rhyme. Or, as my Asian friends might say, “Same. Same. But different.” Let’s get farther into the weeds.

Cheap, Globalized, Multinational Stocks

When Berkshire invested in Japanese trading houses (Mitsubishi, Mitsui, Itochu, Sumitomo, Marubeni) in 2020, these firms were undervalued. They traded at P/E ratios of 5-8x and offered dividend yields of 5%+. These companies were global commodity traders, meaning their fortunes weren’t tied to Japan’s weak domestic economy. Like energy and mining firms elsewhere, they benefited from inflation and rising commodity prices.

Similarly, many DAX multinationals (SAP, Siemens, Linde, Bayer, Allianz) are now valued based on global growth, not Germany’s sluggish economy. These firms generate huge foreign revenues, which are boosted when the euro weakens. Additionally, the market expects ECB rate cuts, increasing valuations and making DAX stocks more attractive.

Market Sentiment: Ignoring Domestic Struggles

When Buffett and Munger bought Japanese stocks, most investors were still bearish on Japan due to 30 years of stagnation. Investors are bearish on Germany today due to high energy costs, overregulation, and deindustrialization. Yet, the DAX keeps rallying.

Weak Currencies Helping Multinationals

The yen’s devaluation from 2020 to 2024 made Japanese stocks attractive to foreign investors. Since many Japanese companies earn dollars from global operations, a weaker yen boosted earnings in local currency terms.

Similarly, the euro has weakened, helping DAX companies that earn in USD. German exporters are more competitive in global markets.

Macro Tailwinds & Low Expectations

When Berkshire bought Japanese trading companies, they were overlooked and cheap. Now, German stocks might be in a similar situation—underappreciated due to deindustrialization fears, but still thriving due to global exposure, ECB rate cuts, and currency effects.

Key Difference: Valuation

Berkshire bought Japanese trading firms at dirt-cheap valuations (P/E < 10, high dividends). The DAX isn’t as cheap—many stocks trade at higher multiples, making this less of a deep-value trade and more of a momentum trade.

Is the DAX Rally Munger’s Version of "Easy Money"?

Yes, for now. In the same way Berkshire made money on Japan, the DAX is riding global macro forces, not Germany’s economic health. However, unlike Japan, German stocks aren’t dirt cheap, so this could unwind faster if global liquidity tightens or recession fears return. Germany’s economy is weak, but its largest companies are thriving globally—just like Japan’s trading houses when Berkshire invested.

Lessons For Americans

There are several key lessons American investors ought to take away from these trades.

First, just because a country’s economy struggles doesn’t mean its stock market will underperform. Investors often focus too much on domestic weakness and miss the bigger picture of how companies generate earnings globally.

For U.S. investors, this means that even if the American economy weakens, major multinationals like Apple, Microsoft, McDonald’s, and Caterpillar can still grow due to strong foreign demand. Exposure to emerging markets through U.S. companies might be more important than domestic growth.

Next, a weak local currency benefits multinational companies by making exports more competitive and increasing overseas earnings when converted back into local currency. If the Fed cuts interest rates and the dollar weakens, U.S. exporters and multinational firms will benefit. In such an environment, sectors with high foreign revenues, such as technology, consumer goods, and industrials, will become attractive. On the other hand, if rates stay higher for longer, investors should focus on companies with strong pricing power and low debt levels to withstand a high-rate environment.

For American investors, the next market rotation could favor undervalued sectors like energy, industrials, and small caps rather than today’s overcrowded AI trades. Valuation is crucial. Contrarian investing pays off—investors should be willing to go against the crowd if the underlying fundamentals support their view.

The biggest lesson is that macro factors often outweigh local economic concerns. Just as Buffett bet on Japan and investors are now betting on Germany’s global companies, Americans should look beyond domestic headlines and focus on U.S. multinationals and overlooked global opportunities.

Wrap Up

This was a longer Rude, but I hope you caught a few stories and the investing lessons that come with them. Thanks again to Dave Gonigam for the idea.

Have a great day!