Posted September 23, 2024

By Byron King

Electricity, Investments, and Your Quality of Life

When I travel by air, I usually choose a window seat. It’s a personal preference; I want to board the plane, stow my gear, scooch into my spot, lift the shade, and look outside.

Often, on the ground, I watch the baggage handlers. They have a tough job out in the elements, humping everything that people pack on a flight. And every now and again, I see a cringeworthy move by which someone’s goods get monkey-slammed onto the concrete.

Then, as we roll down the runway, I watch the placards that indicate how many feet are left until the end of the line. You’ve probably seen them: 8,000 feet, then 7,000, then 6,000, then 5,000, etc. As far as I’m concerned, the sooner we hit the proper speed, rotate, and lift off, the better. I’m always happy to go fast, get airborne, and fly over perfectly good runway.

As we climb out or descend to land, I love to see what’s there. For example, Chicago:

Chicago from the window seat. BWK photo.

Chicago from the window seat. BWK photo.

And how about this long stretch of built-up beach north of Miami:

Miami Beach, looking north. BWK photo.

Miami Beach, looking north. BWK photo.

Then there’s this, in the Colorado prairie east of Denver:

Vast expanse of solar panels. BWK photo.

Vast expanse of solar panels. BWK photo.

Interesting, right? This Denver photo shows solar panels that occupy a lot of land. The whole buildout represents significant investment in real estate, engineering, permitting, equipment, hookups to the grid, all manner of jobs, tax breaks and much more.

This particular array is in high, dry Colorado. There’s nothing out there but sagebrush and maybe some cows (oh, and oil). But it could just as well be rich, fertile, former farmland in Ohio or Indiana, now planted with solar. Or even valuable real estate, such as one might see beneath the approach to Newark. Or, as I saw during recent travels, old cotton patch land in South Carolina now transformed into fields of solar.

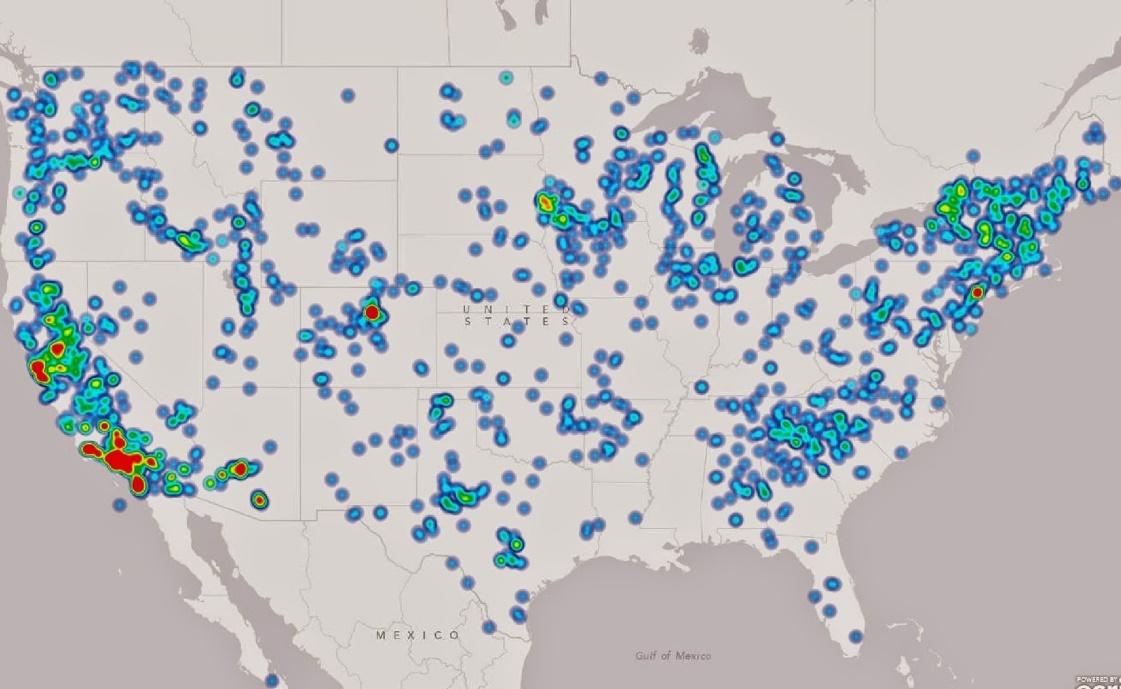

To illustrate the point better, here’s a generalized map showing the density of solar arrays across the Lower 48 states.

Heat map of solar energy spreads across U.S.

Heat map of solar energy spreads across U.S.

Even at this large, kind of arm-waving scale, it’s clear that something big is going on across the country, energy-wise. And unless you pay attention to the biz, the scope of this national-scale solar buildout is probably much more than you might think, even if you look out of airplane windows. And hold that thought…

Let’s Land at Dulles

Following the airplane theme, not long ago, I flew through Dulles International, which serves Northern Virginia and Washington, D.C. Again, per habit, I was looking out the window.

Among the forests, fields, farms, housing, and office park developments, I saw more than a few solar arrays across the landscape. But there was something else as well and a lot of it:

Northern Virginia “hyperscale” data center. Datacenterdynamics.com.

Northern Virginia “hyperscale” data center. Datacenterdynamics.com.

During the approach to land at Dulles, we flew over dozens of massive buildings that looked much like what you see above. One might think these are warehouses and cross-deck facilities for motor freight, but no, the 18-wheelers don’t roll up to unload and reload at the docks… because there are no docks.

Instead, these massive structures are called data centers; the really big ones are called hyperscale data centers. Note (see above) the long, rectangular boxes outside. Those are cooling units, necessary because the innards are filled floor to ceiling with computers and power systems:

Inside a Google data center. Courtesy Google.

Inside a Google data center. Courtesy Google.

What’s the Story?

Okay, so what’s going on inside these large buildings? According to the Virginia Mercury, “Northern Virginia, the densely populated suburbs and exurbs located just outside the nation’s capital, is home to 70% of the world’s data centers, the huge warehouses that store computers’ processing equipment, internet network servers and data drives. With people increasingly using web-based programs on an average of 22 internet-connected devices in homes, data centers are seen to be needed more than ever.”

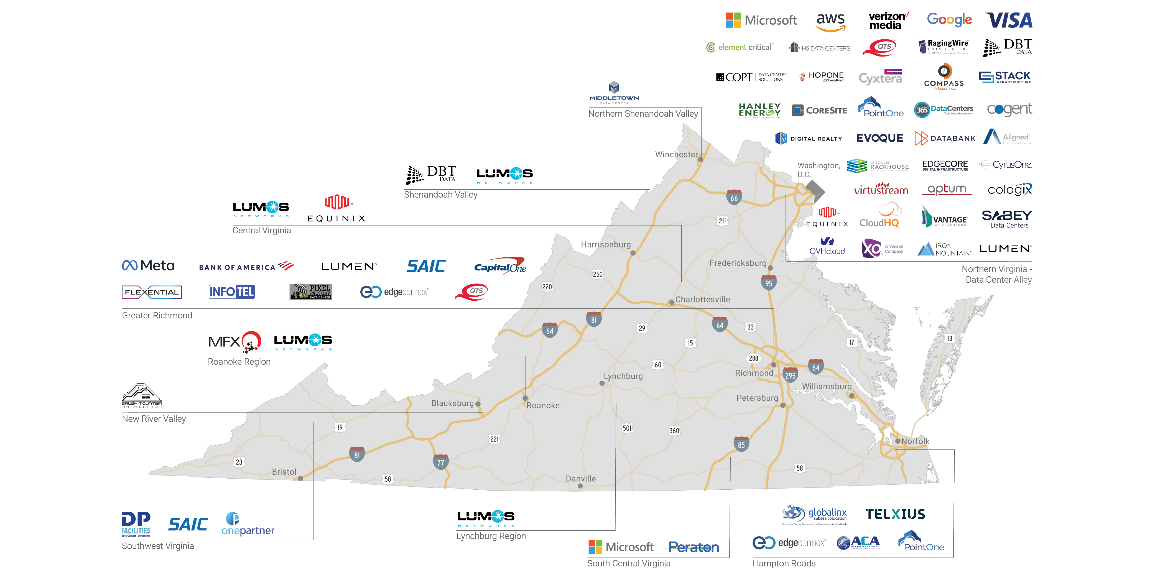

In Virginia, the list of companies (there are many!) that run data centers (again, many!) is nothing short of mind-boggling. If you read this graphic carefully, you’ll see more than a few familiar names and others nearly unknown to mere mortals:

Just some of the data center names. Courtesy Virginia Economic Partnership.

Just some of the data center names. Courtesy Virginia Economic Partnership.

This long list is just a start to the discussion because many companies run numerous data centers. Some, like Amazon and Google, run dozens of facilities, which is why you can go shopping so easily, or “just Google it,” as the saying goes. It’s all that computing power at work.

The overall scope of investment is something that moves the economy. This data center buildout began about a decade ago, and what we see now has created its own world-class economic scale; plus, be assured that many companies are still building.

For example, in Northern Virginia, land purchases have totaled multi-billions of dollars. Construction has run into the tens of billions. And the computers and servers inside those big buildings require a $100 billion capital investment.

Meanwhile, the server designs and chip capabilities required to process all that data have evolved towards increasingly sophisticated levels. That’s why, for example, a company like Nvidia, which leads the pack in terms of certain critical core technologies, has been such a momentum play, bid up into the $3 trillion range of market cap during this past year.

And take another look at those truck-sized air conditioning units outside the centers. What’s their story? Well, a lot of power is required to run the chips and servers, and thus there’s associated heat; it’s thermodynamics at work. Channel big flows of electricity through wires and chips, and the laws of physics dictate electrical resistance, which converts to heat.

On the other side of the energy equation, those data centers require air conditioning and water to cool everything down. And this also requires large amounts of energy, in particular to run fans and pump immense amounts of water or other cooling agents through all the pipes and ducts.

In fact, these data centers use electric power at every stage. Begin with servers and cooling, of course. But also, there’s power consumption for networking equipment and data storage, plus backup and security systems, and don’t forget basic lighting for workers who wander through the rows of equipment, with screwdrivers and pliers in hand.

How much electric power are we talking about? Let’s use familiar ideas and explain by analogy: a server about the size of a briefcase can use as much electricity in one year as a typical house. So take many thousands of servers, and all the rest of the gear inside just one of those big buildings, and you’re looking at an electrical load equivalent to that of a medium-sized town (plus water, too).

Now, take dozens of data centers and hyperdata centers and hook them up. It’s the power load of a large city, and these places operate 24/7/365, pulling electricity from the lines. And what does this mean to the U.S. electric power complex? Well, since you asked…

It’s Still Your Grandfather’s Grid

Generally, and it depends on where you live, the backbone of your regional and local power grid might date back to the 1930s, 40s, and 50s. Yes, it’s that old; in many cases, it’s from your grandparents’ era.

On top of the legacy issue for much of the U.S. power complex, over the past half-century, much of the U.S. electric buildout has been piecemeal and patchwork. Indeed, it’s not wrong to say that, despite all the pontifications and regulations of federal and state politicians and bureaucrats, there’s no real national plan for what the overall power grid ought to look like. It just is what it is.

Still, the lights work, right? You flip a switch and things happen. Yes, because all across the U.S., over 3,000 separate, distinct electric utility companies generate electricity. Some use coal for power, which is more and more frowned upon due to carbon dioxide emissions.

Then there’s nuclear power, which has stagnated in the U.S. for many decades due to political opposition. Hydro, too, although all the good dam sites were long ago built out, and many dams are being demolished due to age, if not for environmental restoration of river systems.

Recently, more and more power plants have been built to burn natural gas; in fact, this segment has grown strongly in the past 15 years or so due to abundant gas from fracking, low cost of fuel, and speed to build. But again, more than a few policymakers oppose natural gas because of the carbon dioxide fixation.

Back to Solar

And so we return to those now-ubiquitous renewable energy projects across the country, visible from the window seat of an airliner: fields of solar. And I didn’t even mention windmills; that's another story.

Obviously, solar doesn’t work at night or in bad weather, and there’s much to say along these lines. One key point is that “renewable” systems (and they are not really renewable) always require backup.

That is, due to what’s called intermittency (i.e., day-night; sunny-cloudy), solar requires a backup method to assure grid quality. This moves us to companion systems like battery storage, if not a gas-fired power plant down the road, sitting at the ready for when the call comes to warm the lines.

When you put it all together — meaning the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth — the point is that sunshine may be free, but the technology systems necessary to harness, store, and use it are quite expensive.

One big takeaway from all of this is that the U.S. is on the cusp of massive new growth in electricity demand, certainly from data centers. Then add in, for example, the fast-growing numbers of EVs on the road that must somehow be charged, plus consider the overall population increase and baseline economic growth. We’re going to need more electricity.

Another angle on this is that, on even the best days, the U.S. electricity complex requires constant care and maintenance because things are always breaking. Then come challenges from rebuilds that are necessary on many fronts, coupled with the new-build energy add-ons now being planned or built and yet to be accomplished.

Is This Investable? Of Course!

We could discuss energy systems and data centers all day, but by now you get the point. There’s much room to invest in the growing build of the U.S. electric grid. And here are a few ideas, but note that, unless noted, they are not official recommendations. If you buy in, use limit orders, watch the charts, buy on down days, and never chase momentum.

First, natural gas: As we discussed, coal, nuclear, and hydro face tough challenges for various policy reasons. Yes, they have a future. But it’s in the out-years, which means that, closer in time, the fastest way to generate large amounts of ready-to-dispatch electric power, either as primary or backup to solar, is with gas turbines.

Along these lines, look for solid plays in the U.S. gas patch. Consider EQT Corporation (EQT), America’s largest gas producer, with an extensive business base in the prolific Appalachian Basin. The company’s market cap is over $19 billion, and shares trade in the $33 range. And the company pays a dividend of about 1.9%. EQT has great growth prospects ahead, to be sure.

Second, look at copper: In previous articles, I’ve mentioned one of the world’s great copper mining companies, Freeport McMoRan (FCX). Shares trade in the $43 range, giving the company a market cap of over $62 billion. And it pays a dividend of about 1.8%. In a rising market for the red metal, Freeport looks good in the years ahead.

Another company in the copper space is Rio Tinto (RIO), with shares trading now at about $62 and a market cap of over $100 billion. Rio pays a dividend of over 6.5% yield, reflecting how much cash it generates in this environment. Again, excellent prospects ahead.

Finally, we must look at silver: Yes, silver because it’s essential to fabricating those above-described solar panels and many of the other electronic systems inside all those huge data centers I described above. Silver is very much an electric metal, for which demand is climbing fast while global output is constrained.

There are many excellent names in the silver space, and I can scarcely begin to list them. However, one that has done quite well is First Majestic Silver (AG), with a market cap of about $1.8 billion. Shares trade at about $6.15, and the company pays a small dividend. As silver prices rise in a high-demand scenario with constrained production, First Majestic shares should do well.

With this, I’ll wrap it up. Remember that, wherever you are in the world, your quality of life depends on the juice in the wires above, below, and truly all around. Without electricity, it may as well be 1824, not 2024. And investment prospects are strong for what makes it all possible.

From Cold War Brilliance to Warmongering Buffoonery

Posted April 24, 2025

By Sean Ring

How a Missed Phone Call May Cost Trump Big

Posted April 23, 2025

By Sean Ring

Charlie Munger’s Mental Models

Posted April 22, 2025

By Sean Ring

The People Who Need and Deserve Our Help

Posted April 21, 2025

By Sean Ring

The Order of Love: Why Nations Must Prioritize Their Own

Posted April 18, 2025

By Sean Ring