Posted July 02, 2024

By Byron King

America’s False Narratives and China’s Industrial Reality

Let’s discuss narrative and reality, but mostly reality; particularly, the reality of Chinese industrial power. Absolutely, this affects your life and the future of the U.S. economy. More to the point, it’s investable and I’ll offer some ideas further along.

First, Let’s Discuss Cars and Trucks

At Paradigm Press, my beat is geology and industry. I cover energy, rocks, minerals, and materials. I keep an eye on concrete, steel, nuts and bolts. In other words, I track people’s ability to make real things. I believe that, eventually, industrial reality will overcome fake narratives. When that happens, you want to be ahead of the crowd.

Sometimes, though, my inner gearhead dominates, and I ponder things like cars and trucks. It’s okay, though, because you can’t do cars and trucks without geology. As my old college professor once quipped, “John D. Rockefeller didn’t invent oil; he invented the oil industry. And Henry Ford didn’t invent the automobile; he invented the automobile industry.”

The professor’s point was that whatever you do, you need energy and basic materials to make it happen. You can’t build cars or trucks without steel, aluminum, copper, lead, rubber, etc. And internal combustion engines won’t work without gasoline or diesel. (Of course, you need roads, bridges, tunnels, etc.; but you can’t build those absent materials, heavy equipment, trucks, energy, etc.)

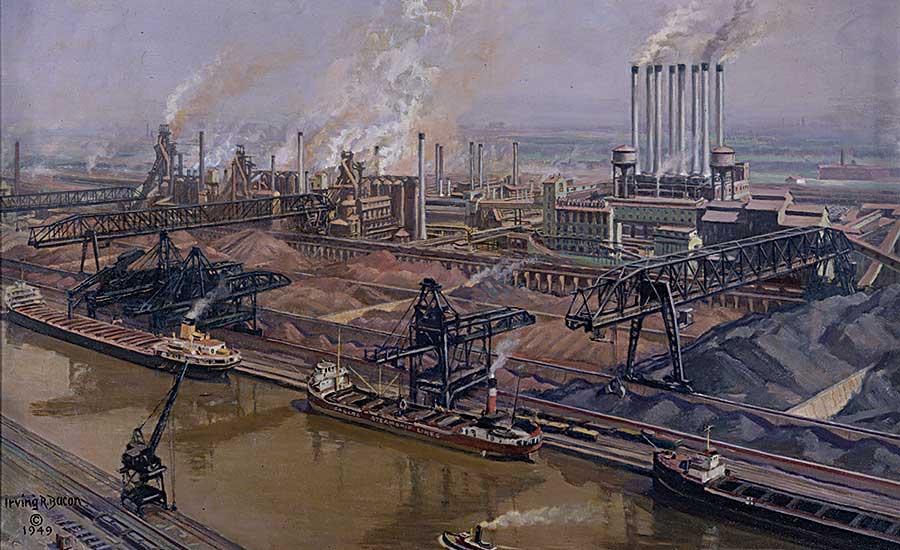

Along these lines, Rockefeller created the 20th century’s industrial model for pumping oil and then refining and transforming it into a myriad of useful energy and chemical products. Ford created the model of an integrated manufacturing company that did everything from mine ore and make steel to roll finished vehicles out the factory gate, depicted below in this painting of the Rouge River Plant.

Henry Ford’s Rouge River Plant. Courtesy Ford Museum.

Henry Ford’s Rouge River Plant. Courtesy Ford Museum.

These business models, Rockefeller’s for energy and Ford’s for auto manufacturing, focused on ways to leverage resources and internal efficiencies. And over the past century, many things have changed on an industrial scale, but not the big picture. You still need materials and energy to build cars, trucks, and pretty much everything else. And you require internal efficiencies to be competitive.

Still, it’s always important to follow change. And right now, there’s a new angle on what the old professor said. To restate his quip, China didn’t invent batteries, but the Chinese have definitely reinvented the modern energy and automobile industries, particularly electric vehicles (EVs).

So, let’s dig deeper into what’s happening and explore this new Chinese industrial reality.

Modern China’s Industrial Revolution

In the mid-1960s, China was firmly entrenched in Mao Zedong's revolutionary era. The country was hyper-politicized through Mao’s crackpot ideas, implemented through the disastrous “Great Leap Forward,” followed by his “Cultural Revolution.”

In general, for two generations after World War II, China misused her people and resources. Consequently, under Mao, the country was so widely underdeveloped that almost the entire nation was an economic basket case.

Zealous, strident Chinese Red Guards, 1960s, feeling good about ruining their economy.

Zealous, strident Chinese Red Guards, 1960s, feeling good about ruining their economy.

Big mistakes have big consequences, and even after Mao died in September 1976, China had to endure years of political and social upheaval. Well into the 1980s, internal factions competed over who would wield power. And today, leadership elements still come and go.

At a more down-to-earth level (literally), a half-century ago, most roads in China were unpaved, even in large cities. To work and move about, most people walked or rode a bicycle. Only the top cadre of political and military power had access to even a basic car, likely a clunker made in the Soviet Union.

But now, let’s hit the fast-forward button. Today, three generations later, China is filled with gleaming new megacities cities where people drive modern cars and trucks across elaborate road networks. No doubt, you’ve seen photos and videos.

Busy Beijing; roads and high rises.

Busy Beijing; roads and high rises.

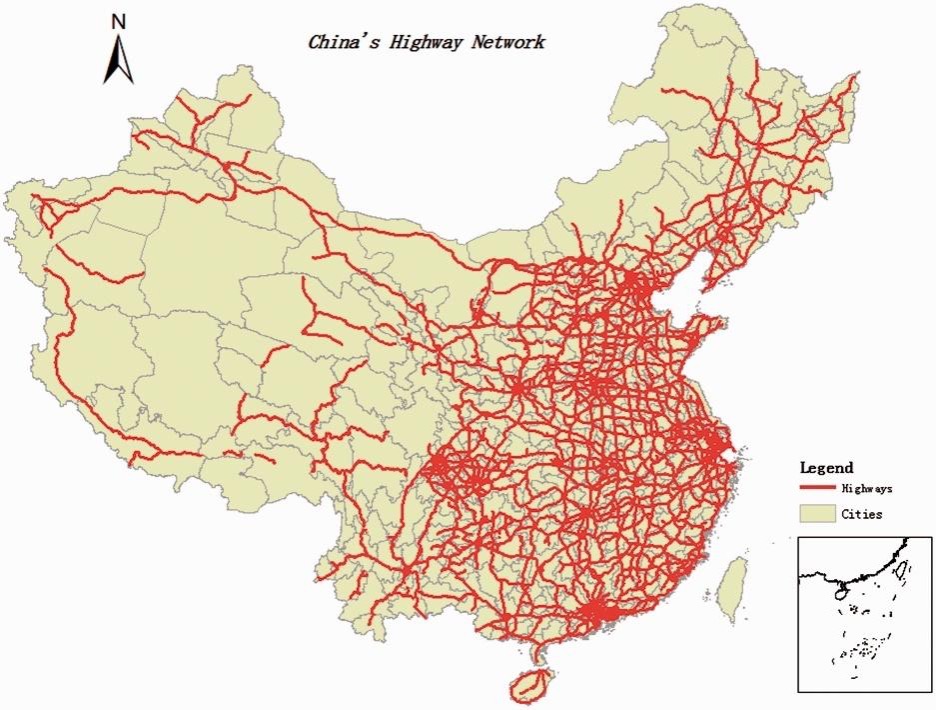

China’s cities are connected by extensive systems of newly constructed highways, with nearly uncountable new bridges, tunnels, and related feats of civil engineering.

China’s half-century buildout of a highway grid. Sagepub.com.

China’s half-century buildout of a highway grid. Sagepub.com.

Of course, we can discern a Chinese-oriented narrative here, all about rapid modernization and industrialization. But there’s also a very credible level of Chinese reality to back it all up, all quite visible within China’s automotive industrial complex.

China’s Really Big Numbers

Today, China’s auto industry has the capacity to build over 43 million vehicles per year. Equally important, China’s energy complex can fuel and power them. This is definitely not the impoverished, undeveloped China of half a century ago.

Of that new-build output, about 25 million vehicles are sold annually in China, the world’s largest market, by far. In comparison, the entire U.S. auto market moves about 17 million vehicles in a good year, and that includes large numbers of non-U.S.-made imports. Plus, the math is that China can build and export about 18 million vehicles per year, over and above domestic sales; again, that’s more exports than the entire U.S. auto market.

China’s vehicle exports go everywhere except for U.S. and Canadian markets. From Jamaica to Djakarta, Lagos to Lima, you’ll find Chinese vehicles. Even London’s storied taxicabs and buses are Chinese these days.

Okay, now for some bullet points:

- China, Inc., so to speak, runs the world’s largest auto industry, which outpaces by far the entire U.S. automotive complex, including all domestic and foreign names. China has an energy complex of comparable scale to power it all.

- China’s auto and energy industries are massively scaled. Everything is big. China has a seemingly endless network of internal supply and manufacturing chains that provide everything involved in building cars and trucks: energy, metals, plastics, electronics, interior items, exterior paints and pigments, and much more.

- Upstream from the manufacturing plants, Chinese supply chains reach deep into many other nations for raw materials that range from oil and coal to mineral ores and primary metals, rubber for tires, and much else.

- In addition to internal combustion engines in traditional vehicles, China clearly dominates the new ecosphere of intellectual property and supply chains for EVs.

- Pertinent to this last point, all EVs worldwide, whether Chinese brands or others, rely almost entirely—about 98%—on rare earth elements (REEs) produced in China; and most EVs everywhere rely significantly—over 80% is a lowball estimate—on Chinese-made battery materials.

Frankly, it’s not a narrative but clearsighted reality to say that Western automakers will have a very tough time in the future. Unlike in the past, Western firms must now compete, at home and abroad, against Chinese products that benefit from those gigantic levels of scale. All this is while China dominates critical supply chains for batteries and related electrical/electronic components, over and above everything else that goes into a car or truck, down to lug nuts and seat belt buckles.

Related to this, an EV is not just a new version of an old car; no, EVs are definitely not what you grew up with. Rather, EVs are electronic systems which means assemblies of electronics and software.

In many ways, they’re far more sophisticated than old, legacy mechanical systems. For example, a typical EV has about 40% fewer moving parts than a similar internal combustion vehicle. And that same EV contains far more electronic components like chips and circuitry, plus highly evolved software.

This electronic angle alone offers another example of China’s large-scale and broad internal efficiency in another significant industry. That is, China Inc. has a robust electronics sector that produces everything from circuit boards and components to large-screen televisions and much more.

The fact is that having a world-class electronics industry literally down the road from automaker design shops greatly facilitates China’s ability to compete globally in EVs, and at an immense scale. Chinese EV firms can easily source homegrown electronic components, unlike the case with the U.S. where most electronics manufacturing long ago moved offshore (much of it to China).

Not Your Father’s Chinese Car

The collective West – certainly the U.S. and its automakers – have arrived at a problematic industrial reality. Namely, in recent years, Chinese EVs have improved in design and quality by leaps and bounds. It’s just a fact that China’s companies build some pretty good cars. (And it’s not me saying it; do a YouTube search for car reviews.)

Image courtesy of BYD Seal, a Chinese carmaker.

Image courtesy of BYD Seal, a Chinese carmaker.

Consider this EV pictured above, a model named Seal (like the marine mammal) produced by a company called BYD. In late 2023, Swiss group UBS hired engineers to tear down a production specimen and see what’s inside and how it all works.

The UBS team dismantled the vehicle down to bolts and wire bundles and compared quality and performance against standard industry benchmarks. The engineers concluded that compared to mass-market EVs from legacy Western makers, BYD “is the better and much cheaper car, thanks to high vertical integration.”

Note those words from the engineers, that BYD is “better and much cheaper.” Uh-oh, you can always buy a better car, but you would expect to pay more for it, right? Except with this BYD, you can now buy a better car – better than Western models – and still pay less.

According to the UBS team, BYD has a 25% sustainable cost advantage over legacy Western competitors, which still allows the Chinese company generous profit margins. BYD has a distinct advantage in the fields of battery cells, vehicle integration, powertrain, and electronics modules. All this, and the BYD driver assistance systems “are also state of the art.”

Again, a large element of BYD’s cost advantage is the overall scale of industry in China and the related internal efficiencies. Yes, it matters when a company can control costs at every step, from ore in the ground to certifying a final assembled unit as it comes off the production line. You can’t “financial engineer” your way out of some things.

Finally, it’s worth noting that BYD was founded in 1995, not as a carmaker but as a producer of batteries and electronics. In 2003, management decided to leverage its skills in power and electronic systems into making cars. Now, BYD is the largest EV maker in the world, bigger than Tesla by unit sales. The company has about 703,000 employees, of which 102,000 (no typo) work in research and development.

This BYD story is like a tech company putting wheels on an iPad, versus Western legacy car companies that currently struggle to put problematic batteries and electronic systems into their old product lines. Good luck to anybody who wants to underprice and outsell BYD.

Would You Buy a Chinese-branded EV?

With all this in mind, would you buy a Chinese-branded EV? And no, I don’t mean a Tesla, about half of which are assembled in China. Nor do I mean Chinese-built models of Western names like, for example, certain Volvo or Volkswagen EVs.

My question is, would you buy an EV built by a Chinese company like BYD, or any of numerous other names? Heck, have you even heard of some of the other Chinese brands? Or if you’ve heard the names, what do you know about them? Because, right now, no Chinese EVs are marketed or available for sale in the U.S., but what if they were?

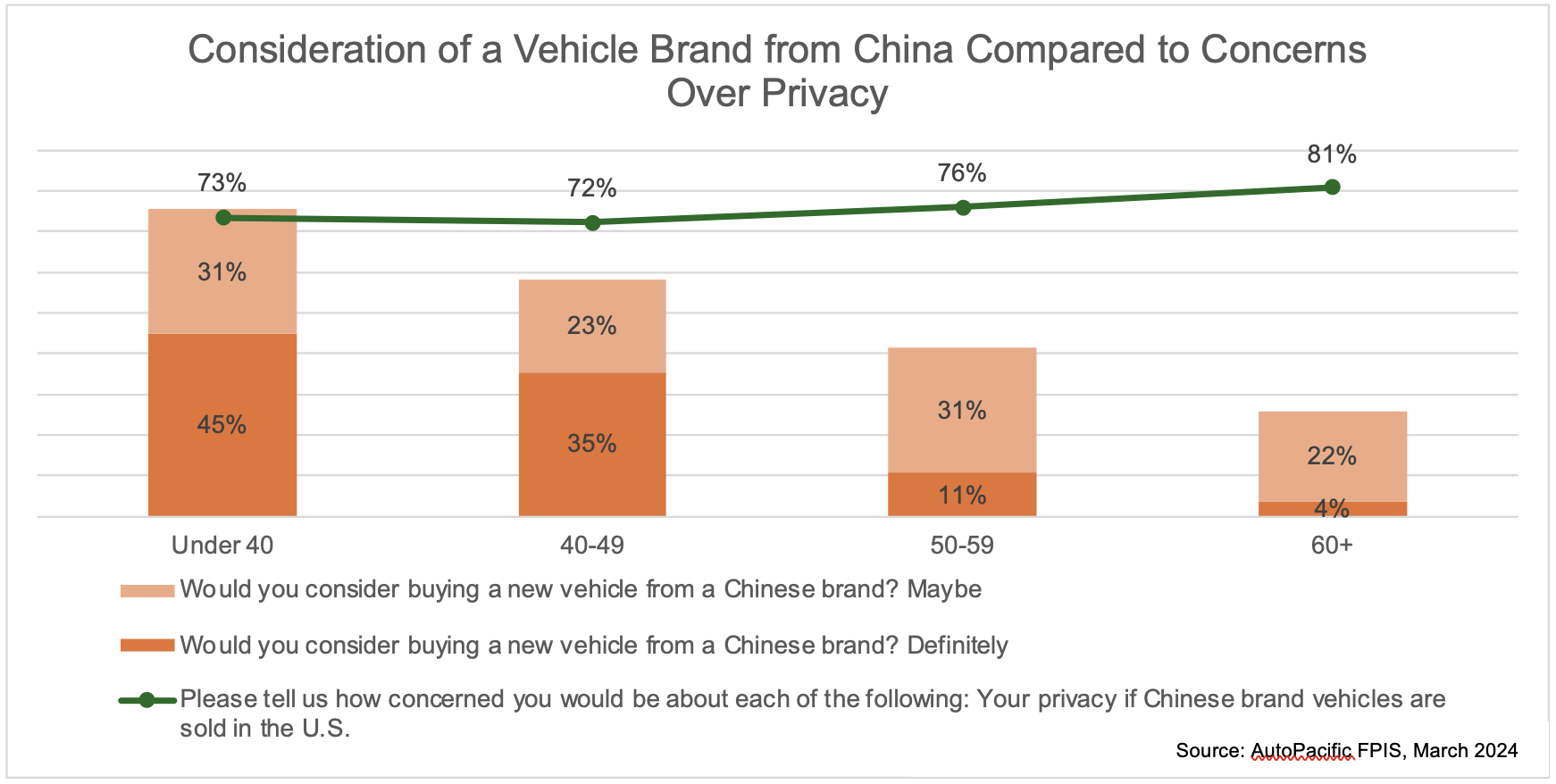

According to a recent survey by the automotive consulting group AutoPacific, U.S. buyers are beginning to accept the idea of buying a Chinese EV. Here’s a graph that lays it out:

About 76% of respondents under age 40 said they would consider buying a Chinese EV. However, acceptance of Chinese brands declines by age; only about 26% of those 60 and older would consider buying a Chinese EV. This issue will inevitably diminish over time as America’s Baby Boomer generation fades away.

And consider the large degree to which young people are open to high-end Chinese products like EVs. Meanwhile, there’s currently a strong anti-China narrative in Western media based, among other things, on military tensions over Taiwan. Plus, there are divisions over trade, intellectual property, and the loss of millions of former U.S. manufacturing jobs that moved offshore to China over the past 30 years.

Despite the anti-China narrative, many Americans remain open to purchasing a Chinese EV. Apparently, they’re familiar with Chinese brands, likely from following social media rather than mainstream news about Chinese EVs. And when China’s EVs hit the shores of the U.S., people will buy them.

Real Industry Beats Fake Narrative

There’s plenty of anti-China narrative out there, depending on where you get your news. But whatever you follow, and as I just outlined above, the industrial reality is that China has built a broad, deep automobile complex that can crank out ungodly levels of cars and trucks. China holds steep cost advantages based on internal efficiencies, and scales of production up and down the supply chain. Again, this does not bode well for legacy Western automakers or their workers and suppliers.

The U.S. response to China Inc. has been for politicians to make a lot of speeches, kick start a new regime of tariffs, and pass two big laws: the Inflation Reduction Act and a companion law concerning infrastructure, both of which involve government subsidies and tax breaks. Thus, goes the narrative, America is moving back onto the rails to success.

But what’s the American industrial reality? Well, we all want U.S. businesses to do well, right? So, don’t count U.S. businesses out, although you must also be sanguine about things. In the 1970s and 80s, post-Mao, China made a plan and has been building industrial power for forty or more years. Meanwhile, here in the U.S., we can barely complete environmental studies within a decade.

Another American reality is culture. The country spent the past forty years deindustrializing, and training two generations of people that there’s nothing wrong with that. So, Americans lost jobs, training pipelines dried up, instructors aged out, schools closed engineering departments, and the country lost much of the social milieu that used to encourage people to move into jobs and careers that involved making things down at the plant or factory.

Of course, the U.S. is a high-cost jurisdiction for business; everything is expensive, including land, labor, regulations, litigation, taxes, insurance, and much more.

Looking ahead, what ought to happen? Well, the U.S. must rebuild vast amounts of infrastructure and basic industry, and do it on a massive, continental scale. All this while protecting old and new firms against being smothered by low-cost imports. And how will that work out? Hey, we’ve come to the end of actual knowledge, and from here on out, it’s all speculation and connecting the future dots. We’re just going to have to figure it out as we move along.

Three U.S.-Focused Ideas

I’ll leave you with three ideas that should do well in the coming years.

First, look at Energy Fuels (UUUU), a metals producer in Utah. Energy Fuels produces uranium yellowcake from ore and thus is a key player in domestic energy. It also produces vanadium metal, which is quite useful as a steel alloying agent and for battery systems. Finally, Energy Fuels just announced the successful completion of a system to recover REEs from ore, making it the only American company with that capability.

Next, look at a name we’ve seen before, Contango Ore (CTG), a gold miner that works in Alaska. Contango has been mining ore all winter and spring, sending it to stockpile at the Fort Knox Mine, near Fairbanks and owned by Kinross. This summer, Kinross will begin processing that ore, and Contango should begin to see cash flow. I expect a serious market upgrade when that happens.

Finally, consider an offshore drilling play in the event that Donald Trump wins the presidential election and changes the approach to development on federal offshore acreage. I like Transocean (RIG), which has a large fleet of drillships and crews. The company stands to benefit from a more petroleum-friendly administration.

Note that these are not official recommendations and will not be tracked in a portfolio. But I watch these companies, and I expect them to do well in the years ahead. If you buy shares, follow the charts, wait for down days in the market, use limit orders, and never chase momentum.

That’s all for now. And remember… stick with reality.

Thank you for subscribing and reading.