Posted June 05, 2025

By Byron King

America’s Aging Air Superiority Ignites Pentagon Spendathon

Soon, President Trump and his team of White House number crunchers will submit a trillion-dollar defense budget for 2026 to Capitol Hill. And there, Congress will slice and dice it via the annual, bipartisan military spendathon.

A trillion is a big number, but it’s no surprise. This new budget is expected to be an expansion of defense outlays from their current level, in the mid-$800 billion range. And set aside (painful, that might be) the country’s chronic issues of national debt and huge interest costs.

The fact is that the Pentagon has a lengthy wish list as this dangerous decade unfolds. At every level, from soldiers in the field to ballistic missile submarines at sea, the U.S. defense apparatus must compensate for several decades of strategic neglect, incompetence, corruption, and blunders by a succession of previous administrations and Congresses.

“Defending the country,” as some call it, offers more than a few investable themes, some of which I’ll highlight below. Meanwhile, despite the increase in cash that'll flow like Niagara through the valves and spillways of the country’s procurement bureaucracy, America’s national defense complex faces immense new, unprecedented challenges, which I’ll also outline.

Victory Through Air Power

Last month, we discussed naval and maritime matters, in particular America’s industrial difficulties in “shipbuilding, shipbuilding, and shipbuilding.”

One key problem is that much of the country’s shipbuilding base has shrunk or closed down over the past three decades. Still, despite and due to these manufacturing and supply chain issues, I presented several ideas for companies that could benefit from increased military spending.

This month, we’ll follow a similar approach, with a focus on air power, along with several investable ideas.

For the past century, the United States has been able to boast of impressive aerial capabilities. There’s plenty of history here, and it was great while it lasted. But looking ahead, the country faces immense new and foreboding challenges. These are apparent from developments in Ukraine, the Middle East, the Far East, and even the recent, short, sharp mini-war between India and Pakistan.

For more background, check the archives of Strategic Intelligence; in particular the September 2022 issue in which I discussed the origins of American air power in World War I, then how it developed in the 1920s-30s, and the singular efforts of a colorful man named Alexander de Seversky, who truly changed the country’s collective mindset about air power, and did so in ways that still resonate today.

“Victory Through Air Power” (Simon & Schuster, 1942). Alexander P. de Seversky was a Russian emigre who became a major in the U.S. Army. His views on air power drove history-making changes in the American way of war. BWK photo.

“Victory Through Air Power” (Simon & Schuster, 1942). Alexander P. de Seversky was a Russian emigre who became a major in the U.S. Army. His views on air power drove history-making changes in the American way of war. BWK photo.

The abbreviated version is that American air power reached its full potential just before and during World War II.

In the run-up to war in the late 1930s, and as the conflict raged, the U.S. mobilized vast sectors of industry to build plants, train workers, establish supply chains, and produce several hundred thousand airplanes of all makes and types. Additionally, the U.S. aviation complex produced war-winning quantities and numbers of spare parts and engines, along with fuel, logistical chains, and entire armies of military pilots, mechanics, and related aviation professions and trades.

All that, and plenty of ordnance to shoot or drop as well.

Postwar, this massive lead in industrial capabilities and human skills kept America dominant in air power throughout the Cold War and into the post-Cold War era. It’s a long story, again with rich history, but I’ll defer that aspect for now.

Fleets of Old Airplanes

Today, of course, U.S. military air power spans the globe, most visibly through the U.S. Air Force and its numerous aircraft and capabilities, as well as the flying warhawks of our Navy and Marine Corps. Additionally, there are Army aviation, Coast Guard aviation, and various aerial capabilities within numerous so-called “other government agencies,” which range from the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) to the National Reconnaissance Office (NRO), as well as a long list of related alphabet-soup organizations.

Here's some eye candy to help set the stage and make a critical point. The U.S. has immense capabilities in areas such as long-range transportation, using gigantic aircraft like the venerable C-5B or C-17.

USAF C-5B (above) and C-17 transports. USAF photo.

USAF C-5B (above) and C-17 transports. USAF photo.

The U.S. also possesses powerful, long-range strike capabilities through its venerable B-52, B-1, and B-2 bombers.

USAF B-1 (lower left), B-2 (left), and B-52 (top) bombers. USAF photo.

USAF B-1 (lower left), B-2 (left), and B-52 (top) bombers. USAF photo.

Additionally, the U.S. possesses astonishing capabilities in aerial surveillance through seldom-seen systems that gather intelligence or use other powerful airborne technologies to monitor the air and ground situation.

USAF RC-135W “Rivet Joint” surveillance aircraft. USAF photo.

USAF RC-135W “Rivet Joint” surveillance aircraft. USAF photo.

Then there’s the “tactical” side of things, such as fighter-bombers like these:

Left to right, F-35, F/A-18. F-16, F-22, F-15. USAF photo.

Left to right, F-35, F/A-18. F-16, F-22, F-15. USAF photo.

And crucial to it all is the capability for aerial refueling, which extends mission times and ranges, and enables all manner of tactical, operational, and even strategic flexibility.

USAF KC-46A (left) and KC-135 refueling tankers. USAF photo.

On this last point, one phrase sums up quite a bit of modern American air power; a pithy line that refueling aircrews use to drive home a key idea to everyone involved in mission planning and execution: “There’s no kicking @ss without tanker gas.”

With this in mind – and apologies to those whose favorite airplanes I left out! – Let’s also note that almost every aircraft you see in the images above is old. Sure, they’ve been maintained and upgraded over the years. The paint is fresh, but the bare bones and fundamental designs of these platforms are many decades old, dating back to half a century or more in some instances.

For example, consider that the last B-52 rolled off the assembly line in 1962, while many KC-135 refueling planes are also of 1960s-70s vintage.

Of more recent origin, B-1s date back to the 1980s-90s; B-2s are from the 1990s; many F-15s and F-16s are also from the 1980s-90s; and most F-22s are 20 years old or older.

Meanwhile, the U.S. no longer has a workforce or assembly lines to build large transports like the C-5 or C-17, which means that the Air Force will fly these birds until they age out, with no replacement in sight.

Stated another way, and as an Air Force acquaintance once pointed out, “It’s not your father’s Air Force, and it might be your grandfather’s airplane.”

The New Face of Air Power

Now let’s address some tough lessons learnt from developments in Ukraine, the Middle East, and more.

First and foremost, we live in a new military age. Traditional air power – those haze-gray warbirds – no longer controls the sky. Indeed, aircraft everywhere now share airspace with long-range missiles and highly capable drones, leading to another problem: there is no such thing as “operational depth” anymore.

That is, the olden days of war involved well-defined lines of contact where troops from each side faced off. It could be a hard line on the map, like trenches in World War I. Or the conflict space might be battle zones with few dug-in positions, but still recognizable areas of control, such as those found in the island campaigns of the Pacific during World War II.

Still, until recently, the idea of a wartime “front” was a well-defined concept. There was a distinct combat zone where the bulk of fighting took place, while rear areas were relatively safe; well, “safe” once you were out of artillery range, and also if the other side didn’t have much reach in the way of air power. (Think in terms of the Korean War, Vietnam, Desert Storm, Afghanistan, and Iraq 2.0, where U.S. and allied forces had mostly secure rear areas.)

Well… I hate to break the news, but that’s no longer the case.

Consider the past three years in Ukraine. There, Russian missiles have routinely traversed hundreds of miles of territory and traveled far behind the front lines to strike with remarkable accuracy. Couple this with excellent reconnaissance and intelligence, plus highly competent target selection, and nothing of value is safe in the rear.

In essence, if the other side has targeting coordinates, it’s only a question of time (often, a very short amount of time) before something explosive lands on point. “Warheads on foreheads,” some call it.

Since the beginning of the Ukraine conflict, we’ve continuously seen large numbers of effective Russian strikes at operational depth against supply areas, transport hubs, staging grounds, training centers, airfields, intelligence centers, industrial sites, and much more. And while some Russian missiles and long-range drones have been shot down, many made it through to hit where they were aimed. And the onslaught continues today.

Right away, we have a deadly problem for U.S. air power, which has evolved to rely on secure rear areas for hangars, maintenance, runways, fuel, weapon storage, staging, and much else.

For example, over the past 18 months in Ukraine, more F-16s have been destroyed on the ground, just parked at airfields, than have been shot down during combat missions. Which is another way of saying that, among many reasons, F-16s have been militarily useless for Ukraine against Russia.

Meanwhile, U.S. and Western air defenses have spectacularly failed in Ukraine, particularly against modern Russian cruise and ballistic missiles and certainly against those now famous (or infamous) hypersonic rounds like Iskander and Kinzhal, two varieties of super-fast missiles.

One embarrassing air defense failure was the super-expensive (at about a $billion dollars per system), highly touted U.S. Patriot complex, which has been nearly worthless in combat against Russia’s fast missiles. Based on unclassified reports, almost all Patriot batteries that the West has sent to Ukraine have been damaged or wrecked.

“Deciders” Made Bad Decisions

So, why are U.S. air defenses so poor? Because, frankly, the country’s military planners spent the past 35 years not worrying much about fighting an opponent equipped with advanced aerial attack capabilities. After all, the accepted gospel was that America dominated the post-Cold War world. The U.S. was on top of things and would remain there.

Then again, it’s not that U.S. intelligence gatherers didn’t, for example, monitor and track tests of, say, new and better Russian missiles. No, at many levels, American analysts saw, understood, and reported exactly what was happening.

However, as generally accurate, field-level intelligence moved up the political food chain, top “deciders” in the U.S. planning system failed to address the looming threats of new aerial attack and defense technologies. They failed to understand what the evidence clearly revealed was coming. And this high-level failure of military imagination was bipartisan, to be sure. From the administrations of G.H.W. Bush, through Clinton, W. Bush, Obama, Trump 1.0, and then Biden, the U.S. suffered two generations of post-Cold War, “end-of-history,” flawed operational and strategic thinking.

One plausible explanation is that the lapse in preparation and technology investment reflected a long-term and unfortunate cultural bias in America against studying proper military history and related military science; it’s an actual national failure within both civilian and even military education pathways. Whatever the reason, however, the fact remains that for three decades, the policymaking crowds of Clausewitz wannabes at the top of government lacked the mindset to process what was right in front of them.

Sad to say, over the long term, the U.S. failed to upgrade its air defense systems based on good intel. Meanwhile, out in the field and conflict zones across the world, believers in U.S. air power doctrine assumed, as a given, their unfettered ability to operate generally in protected rear areas. If you were around back then (and I was), many senior people genuinely believed that the “next war” would be just another Desert Storm.

The takeaway right now is that America’s longstanding, near-religious belief in air power – a legacy that goes back to de Seversky in the 1940s and before – has reached a failure point. That is, there’s no further assurance of airspace security at operational depths where aircraft and munitions are berthed, serviced, and prepared for combat.

This is not just an American problem, either. For example, a similar air defense problem confronts Israel, which has become an open target zone for barrages of relatively primitive ballistic missiles fired from Yemen by the Houthis. Routinely, when missile warnings go off, Israelis must head for the nearest bomb shelter while the Houthi missile almost always hits in or around where it was aimed; eg, Ben Gurion Airport or the Port of Haifa.

If nothing else, this lack of aerial defense is choking the Israeli economy. And despite whatever propaganda you might see (often based on archival footage of old encounters), Israel’s “Iron Dome” system has been a failure in most instances versus high-speed missile attacks from Yemen.

Meanwhile, advanced radars and electronic warfare have further eroded America’s long-term advantage in air power. Russia and China both have radar systems that look “over the horizon,” so to speak, and can track aircraft almost from the moment of takeoff roll.

In general, America’s military competitors have technology that utilizes specific frequencies and systems with the capability to track even so-called “stealth” aircraft. Then, their advanced fire control systems can deliver a high-probability kill solution. (Recall how a U.S. F-117 was shot down by Serbian air defenses back in 1999, using Soviet-era equipment; and newer tracking and fire control equipment from Russia is even better.)

Or consider what we just saw between India and Pakistan, in one of the largest aerial battles in the world since World War II. Using Chinese fighters and missiles, Pakistan claims to have shot down several Indian aircraft, including advanced French airplanes, although India denies this. Meanwhile, the Chinese are gloating and smirking over the success of their armaments.

From the other end of the fight, India launched a large number of effective air strikes on Pakistan that wrecked numerous airfields and other targets, which means that almost all of India’s missiles broke through Pakistani radar, electronic, and kinetic defenses and disabled Pakistani air power on the ground.

In short, the new environment for air power presents a maze of heretofore unseen constraints that, at the very least, complicate the mathematics of force projection, let alone defense. Begin with the lack of operational depth, and then add effective tracking by enemy radar, as well as enemy electronic warfare that confounds everything from navigation to weapon targeting, and vulnerability to new classes of interceptor missiles.

Not only is it “not your father’s Air Force” anymore, but it’s also not your grandfather’s air power environment either.

The Looming Defense Spendathon

Don’t think for a moment that U.S. defense planners are currently unaware of any of what I just laid out. Ukraine has served as a serious wake-up call, alongside what has become increasingly evident in the Middle East, as well as in South and East Asia. Of course, people write papers and books on these issues, most of them highly classified for reasons that are not hard to discern.

On my end, I’m speaking as a retired U.S. Navy officer, currently a civilian, and expressing my personal opinion based on publicly available information. I’m making nostatementson behalf of the Navy, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government.

So, with that said, let’s return to the Pentagon’s looming trillion-dollar spending spree for new equipment and systems, within a procurement bureaucracy that is also a legacy of the 1960s, as we mentioned the venerable B-52s above.

The Air Force is acquiring a fleet of a new type of bomber called the B-21, featuring a range of advanced capabilities. The prime contractor is Northrop Grumman (NOC), with many subcontractors. This program will become a Northrop cash stream that will extend for 25 years or more, well into your investment future. Northrop is also the prime contractor for a new generation of intercontinental ballistic missiles that will replace the 1960s- and 1970s-era Minuteman system, a long-term program.

Meanwhile, Boeing (BA) is building a fleet of new tanker aircraft, the KC-46A, although the program has been deeply troubled by engineering problems and cost overruns. Still, this is the only game in town for tankers.

Also, President Trump recently announced that Boeing will be the prime contractor for a “next generation air defense” aircraft (NGAD), essentially an advanced version of the older F-22, but incorporating numerous advanced features of the F-35, whose prime builder is Lockheed Martin (LMT).

Remember also that Saudi Arabia is making strategic moves in the aviation sector, and just placed substantial orders as it seeks to compete with its Gulf neighbors. On the civil side, leasing firm AviLease recently announced the purchase of 30 Boeing 737 MAX jets, following a visit by President Trump to the region. This acquisition is part of Saudi Arabia's broader strategy to diversify and expand its aviation capabilities.

Meanwhile, Boeing is also receiving funds for advanced versions of the sturdy old F-15, now extensively upgraded with many modern features. While in terms of fighter-bombers, Lockheed will still build more F-35s.

Powering the aircraft are engines by General Electric, now known as GE Aerospace (GE), as well as the former Pratt & Whitney brand, now part of Raytheon, which has been renamed RTX Corp. (RTX).

RTX is a key builder of aerial munitions, ranging from the relatively short-range Sidewinder to the longer-range Advanced Medium-Range Air-to-Air Missile (AMRAAM). And then there’s an even longer-range item still in development, designed to fly to “operational depth” of opponents as well. And Lockheed, too, is a key supplier of various missiles.

There’s much more to say, and we’ve barely scratched the paint of many other military programs in the arenas of command, control, communications, intelligence gathering, and data processing to the level of artificial intelligence (AI) and quantum computing. Companies in the forefront range from L3Harris Technologies (LHX) to the venerable IBM (IBM).

Is there more to say? Absolutely, way more, but I’ll end here. Please note that none of the companies I mentioned are “official” recommendations, and we won’t track them in the portfolio. But it’s easy to foresee solid investment prospects for all of them. Just be sure that if you buy shares, you wait for down days, use limit orders, and never chase momentum.

That’s all for now. Thank you for subscribing and reading.

Dollar Dumps, Everything Pumps

Posted July 01, 2025

By Sean Ring

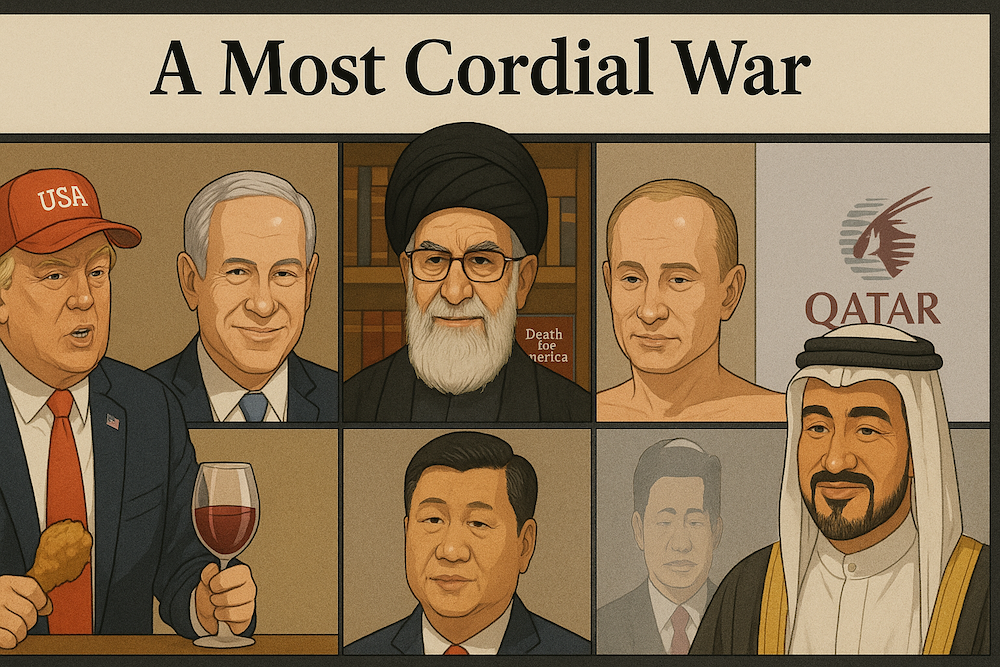

“That’s A Disgusting Assessment of the Conflict!”

Posted June 30, 2025

By Sean Ring

Oh, Cry Me a Canal!

Posted June 27, 2025

By Sean Ring

“You Better Get A Big Shovel!”

Posted June 26, 2025

By Sean Ring

مرحباً بكم في مدينة نيويورك!

Posted June 25, 2025

By Sean Ring