Posted July 15, 2025

By Byron King

Weapons of Mass Importation

In this article, my focus – and the related investment theme – is on the metals of Mars, the ancient Roman god of war, not the Red Planet. (I’ll leave that to Elon Musk.)

In an allegorical sense, they are the “precious metals” that matter these days, especially to fight wars.

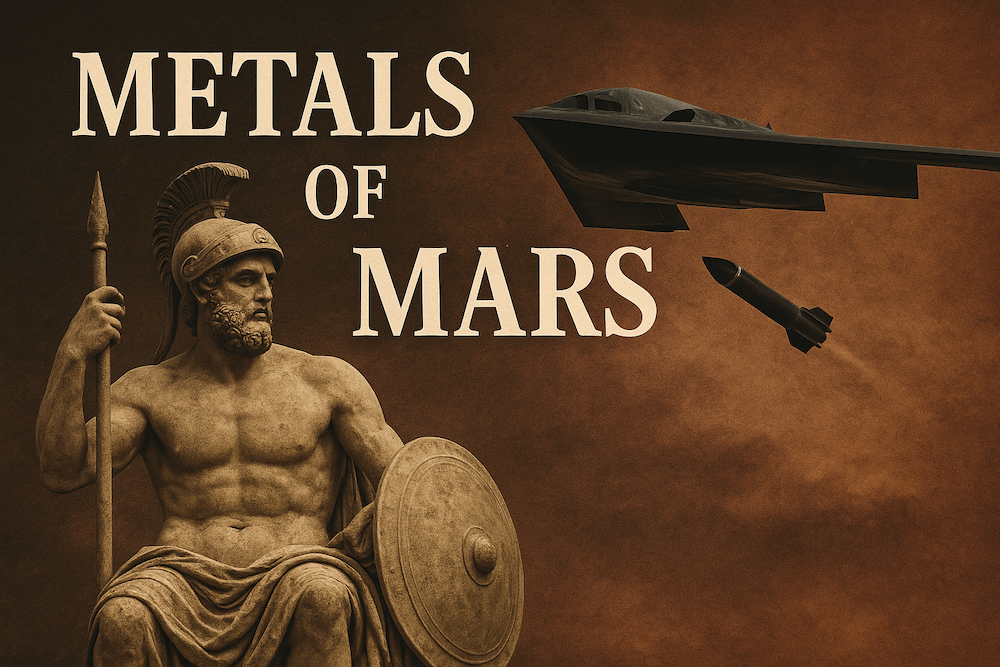

Colossal Statue of Mars. Courtesy Capitoline Museum, Rome.

You Don’t Fight Wars “Only” With Money

When we usually discuss precious metals, we mean gold, silver, platinum, and palladium. And yes, these metals are crucial to war, especially paying for it. And obviously, it takes money to fight a war. As Sun Tzu pointed out in his classic Chinese work, The Art of War, “Wars cost much silver.”

In his ancient treatise, Sun Tzu described the immense costs of horses and chariots, bows and arrows, swords and lances, armor and other equipment for soldiers, as well as food, tents, other provisions, and salaries. And with this in mind, he also sagely pointed out that, “No nation has ever benefited from a long war.”

But also within Sun Tzu’s description of the cost of war, he makes a critical distinction, namely that you don’t fight wars only with money. Those horses, chariots, swords, and lances weren’t made out of silver; they were made from suitable materials that were available at the time, all of which had to be produced, procured, and delivered at some level of industrial scale, in one form or another.

Moving ahead in history, from Sun Tzu’s China to ancient Rome, consider that sculpture of the war god Mars, above. It’s an artist’s view of what was necessary to wage war back then; familiar items like leather and iron, bronze (an alloy of copper and tin), lead, and perhaps some silver or gold as decoration on a helmet or scabbard.

This is all great history, but a modern inquiry into the precious metals of Mars requires us to look at very different materials. Indeed, in what follows, we’ll discuss metals from the periodic table that weren’t dreamed of until thousands of years after China’s Sun Tzu and Rome’s Mars. And indeed, most of these substances have not become available, let alone crucial to people, until the past 75, 50, or even 25 years or so.

What Is Your Image of Warfare?

No doubt, you followed the news about the recent war between Israel and Iran. It was hard to miss accounts of Israeli F-35I jets dropping precision-aimed munitions, and Iranian missiles roaring back at Tel Aviv. Then, American B-2 bombers dropped so-called “bunker buster” bombs.

B-2 bomber drops GBU-57 “bunker buster.” Courtesy Dept. of Defense.

Or perhaps, this past May, you followed news from India-Pakistan, about the short but sharp clash between those two nations. It was a massive air war, fought at long ranges by ultra-sophisticated, high-end missiles.

And of course, the world has changed in innumerable ways over the past four years due to the conflict between Russia and Ukraine, involving essentially all of Europe, the U.S. and Canada, nations from the Middle East, China, and more. Two signature weapons in the military operation have been hypersonic missiles and mass-produced drones that have become better and better with each passing month.

Meanwhile, we’re living through an ongoing naval and aerospace military buildup all across East and Southeast Asia. That part of the world is no longer known just for bargain-priced shopping malls that sell consumer electronics and clothing. The geography is now a vast coastal and oceanic space of artificial islands, radar tracking stations, missile batteries, and submarines.

These actively kinetic, and/or early-but-budding military confrontations between nations recall another old line from a scholar of martial thought, Leon Trotsky, who noted that “You may not be interested in war, but war is interested in you.”

Weapons Are the Sum of Supply Chains

In previous articles, I’ve discussed how any nation’s military power is the first derivative of its industrial power. This idea is straightforward. You can’t build, say, tanks or ships without steel, and for that you need energy, iron ore, steel mills, and much else in the way of machine-building and parts-making. Only then can you build your tank or ship.

Just consider how, during World War II, the U.S. became a so-called “arsenal of democracy.” Things worked out for America – and only worked out – because by the late 1930s and early-40s the country had vast resources of energy and minerals, plus mines, mills, refineries, and factories. America could make stuff, and in large quantities.

Plus, in the late 1930s-40s, the U.S. had a national-scale workforce that government planners – specifically, the old War Production Board – could shift over to wartime work in defense plants, shipyards, aircraft sheds, and more. (for example, see: Paul Kiostinen’s 2004 book, Arsenal of World War II: The Political Economy of American Warfare, 1940-45; or A.J. Baine’s 2014 book, Arsenal of Democracy: FDR, Detroit, and an Epic Quest to Arm an America at War; and of course, many other similar works that rest on an entire historical-economic field of research.)

In other words, those weapon systems that became end products in the Second World War were the sum of many supply chains. And that was then, back in the 1940s; a situation that carried over into the U.S. defense complex through the 1950s, 60s, 70s, and into the 80s. (Of course, the Soviet Union’s centrally planned, wartime industrial system also evolved for nearly half a century as well.)

So, the good news is that America’s wartime legacy lasted many decades. But the bad news is that, frankly, that old legacy is no longer the current military-industrial state of affairs. The problem for the U.S. is that, over the past four decades, innumerable and critical supply chains have become globalized. This has elevated risks of material scarcity, if not total unavailability, deep into the overall engineering and production effort.

As things stand right now, the U.S. cannot generate large swaths of critical components that form the core of many weapon systems.

This predicament is shocking, horrible, and disgraceful on a national scale. For several decades, the country’s politicians, planners, futuristic thinkers, and money-grubbing corporate managerial class have failed us en masse. But don’t just take me saying so.

No less than the authoritative trade magazine Aviation Week & Space Technology recently published an article in which it explained how Chinese suppliers alone “affect more than 1,000 Pentagon weapon systems and more than 20,000 individual parts.” And this statistic – note the nice, round numbers! – is likely on the lowball end of how bad it really is; we’ll find out for sure eventually, when the real war begins. (Okay, yes; hope & pray that it doesn’t. Meanwhile, pass the ammunition.)

Look Under the Hood… for Supply Chains

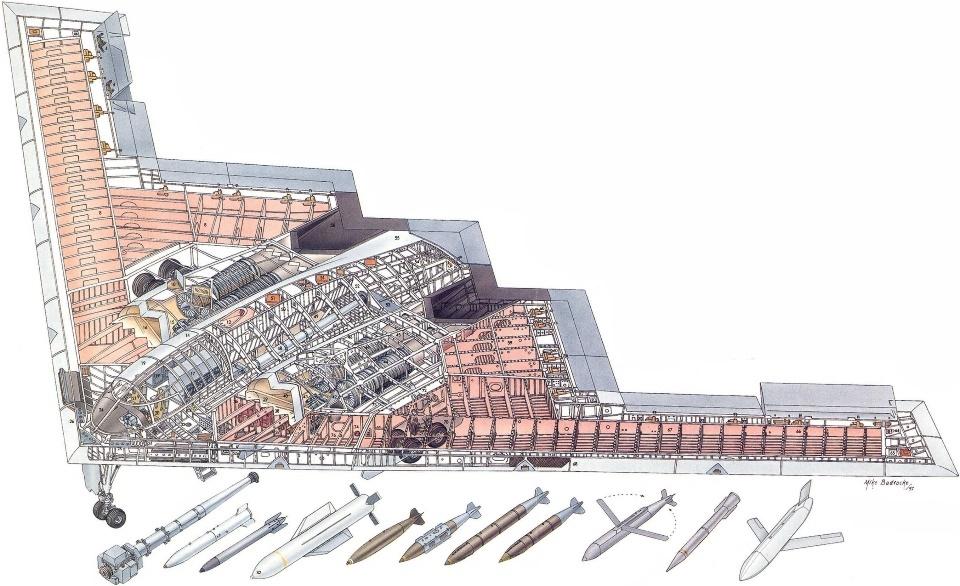

To illustrate the problem and help to wrap our collective brain around it, let’s peer past outward appearances. That is, when you look at an Army tank, or a Navy ship, or an Air Force fighter jet or bomber, what do you see? Yes, of course, you see a tank, a ship, a fighter jet, or a bomber. But it’s also important to think deeper because everything is a collection of supply chains.

For example, look again at that image above of the B-2 bomber dropping the GBU-57. The aircraft is a collection of aerospace-grade steel, aluminum, titanium, carbon fiber, ultra-exotic electronics, and so-called “stealth” coatings made of… umm… exotic materials, which is all I can say on that point. Here’s a cutaway view for more perspective:

B-2 bomber, internal cutaway view. Courtesy Reddit.

And that big “bunker buster” bomb is also quite an article of high-tech design and materials. Just the steel casing alone is an iron-cobalt-nickel alloy that includes numerous additional elements to add strength and durability; enough for the device to penetrate 200 feet of solid rock, according to the Pentagon press releases.

An American steel mill, located deep within the heartland of the Republic, cast that remarkable alloy into a cylindrical shape via very creative metallurgy. I’ve visited the production facility, and let’s just say that you won’t find this kind of engineered metal for sale down at your local drill pipe and bar-stock vendor.

GBU-57. Courtesy Defensefeeds.com and Jim Mumaw.

Meanwhile, the penetrating tip of the BLU-57 is a tungsten alloy, while the explosive filler is an exotic mix of chemicals, fused and triggered by components that are rich in antimony. All this, while the electronic guidance system uses numerous rare earth metals, and the steering fins that guide this monster rely on high-strength rare earth magnets.

Okay, you get the picture.

Whether it’s a launch platform like a ship, aircraft, wheeled or tracked vehicle, or whether it’s the ordnance itself that goes “boom,” modern military systems only work because they utilize exotic elements and materials, alloyed and formed into high-tech components. This description covers pretty much everything from airframes and bomb casings to explosive packages, as well as electronics, guidance, and much more. We’re a long way from ancient Chinese or Roman soldiers whacking on their opponents with long sticks that they trimmed from tree branches.

We could go through a list of many thousands of U.S. weapons, from air-to-air missiles to high-power microwave generators, lasers, night vision, and more, all the way to massive electric motors that drive submarines, and antiballistic missile defenses. And the sorry state of the American industrial story would be much the same. Namely, this is not the 1940s anymore. For an astonishing array of critical materials, the supply chains just aren’t there.

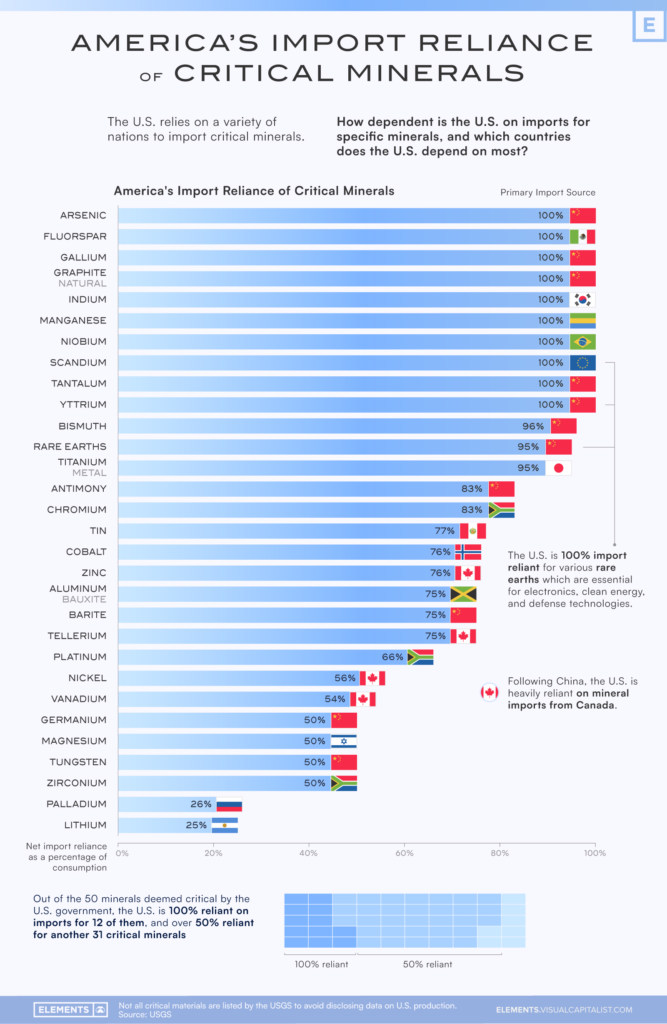

Modern weapons require materials from deep within the heart of the periodic table, but, for the most part, U.S. industry cannot produce them. This graphic illustrates how many basic materials the U.S. does NOT produce. And note how many of these materials come from China, which is no accident because China has been thinking decades ahead for a long time.

U.S. import reliance on critical materials. Courtesy Mining.com.

So, Who Is Doing What?

The good news is that the Pentagon and U.S. industry have caught onto the problem. In a macabre sense, it “helps” that in recent years China restricted or embargoed exports of certain elements and materials to U.S. customers, particularly defense giants like Boeing (BA), Lockheed (LMT), Raytheon/RTX (RTX), Northrop Grumman (NOC), and many more. Like a hit on the head with a 2-by-4, the problem has become real and apparent.

And it’s not just defense companies behind the 8-ball, either. Numerous Western industries have had to scramble for China-sourced materials—these range from U.S. automakers to electronics companies, chemical companies, even pharma, and many more.

One large mining company that has moved smartly to produce exotic elements is Rio Tinto (RIO). Within the past few years, this giant has added capacity to produce a metal-alloying element called scandium from its titanium mill in Quebec, and to produce an element called tellurium, used in electronics and solar panels, from its Bingham Canyon copper mine in Utah. So yes, these things can happen when people decide to invest and do them.

More recently, in May, RTX announced plans to produce gallium in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) with a company called Emirates Global Aluminum. No, it’s not domestic production in the U.S. But right now, gallium is critical, and China has shut off supplies. So RTX is desperate for material, and yes, it’s that bad.

For RTX, this gallium is indispensable for gallium-nitride (Ga-N) semiconductors, which outperform silicon chips in speed, power, and endurance in extreme temperatures. For many years, RTX has been a leader in Ga-N use in military radars, such as the Army’s Patriot missile system and its Terminal High-Altitude Area Defense system (THAAD), and the Navy’s Aegis air defense complex. But again, China shut out RTX, and now it’s a catch-up game.

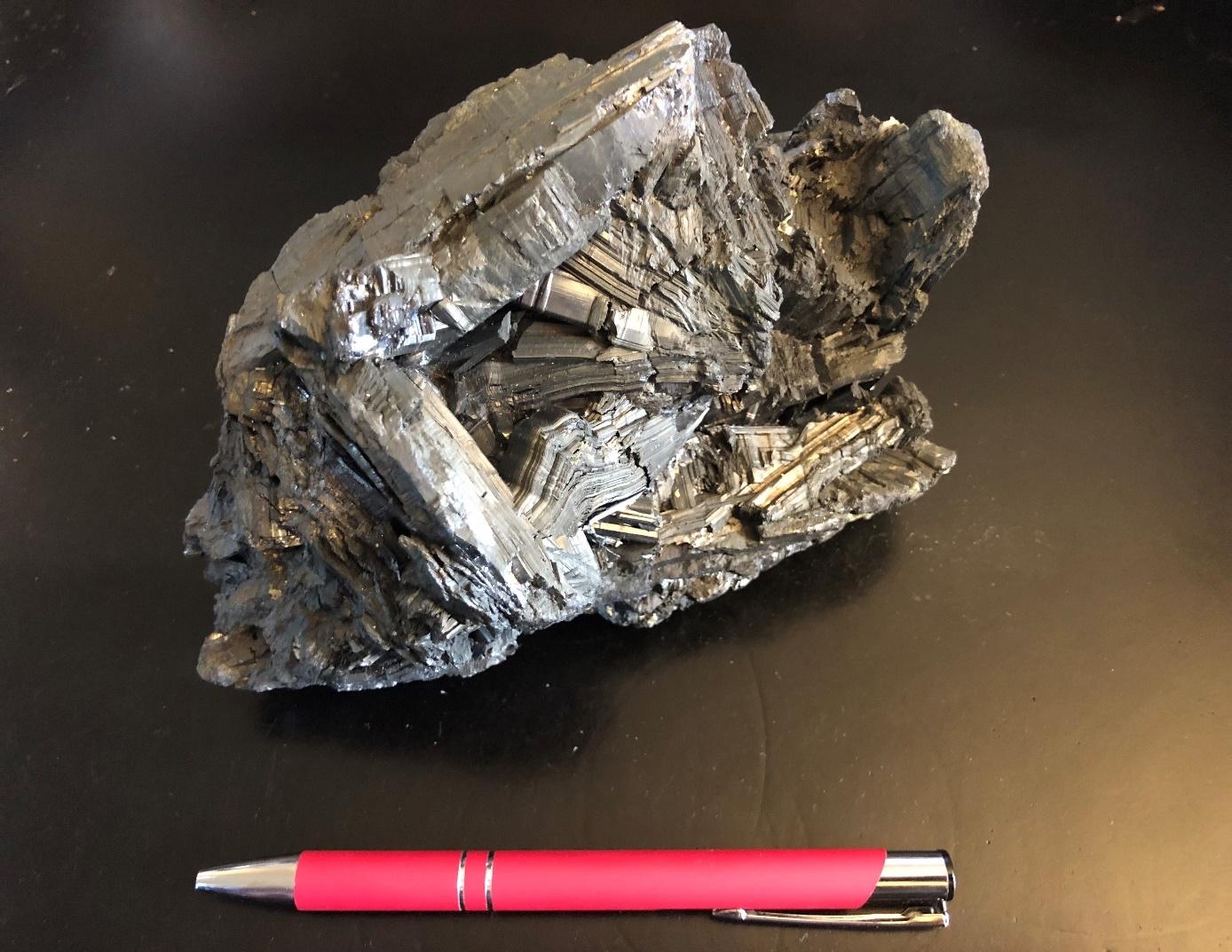

Another element on the China embargo list is antimony, most of which comes from the mineral stibnite. Current U.S. production of stibnite/antimony is zero.

Antimony-bearing stibnite mineral. BWK collection.

Among other uses, antimony is essential in two key areas, namely fire-resistant materials and ammunition primers. Indeed, absent antimony, we’re almost back to using flintlock sparks to set off gunpowder in rifles, and the bombs, rocket motors, and much more won’t work, either.

One U.S. company is working on a significant stibnite-antimony project in Idaho, namely Perpetua Resources (PPTA). The stibnite (and gold) deposit was mined many decades ago, and is a well-understood ore deposit, so overall it’s a promising future source of metal. Plus, for reasons not hard to understand, this group has received financial backing from the U.S. government. Still, the project is pre-development and pre-revenue, but it’s making progress.

All this, and I’ll mention three other antimony plays that I’ve followed, although they’re relatively small at this stage, and risky in the sense that they are true mining “juniors.” All are pre-production, and still well within what we call advanced exploration/early development stages: U.S. Goldmining, Inc. (USGO), with stibnite associated with gold in Alaska; Rua Gold, Inc. (NZAUF), with stibnite associated with gold in New Zealand; and Military Metals (MILIF), with a well-understood and significant stibnite deposit in Slovakia (a deposit which I visited last fall).

There’s plenty more to say about the precious metals of Mars, because there are many other critical metals in the periodic table. But this is already quite a bit to absorb, so I’ll wrap it up here.

I hope you’re getting the key point here: geopolitical tensions are escalating, and the U.S. needs to reduce its reliance on foreign sources of critical minerals, particularly those from China.

The Flash That Created Our World

Posted July 18, 2025

By Byron King

Patience is a Precious Virtue

Posted July 17, 2025

By Sean Ring

Liberté, Egalité… Guillotine?

Posted July 14, 2025

By Sean Ring

The Devil’s Metal Rises!

Posted July 11, 2025

By Sean Ring

Brazil Pays for Prosecuting Trump’s Buddy

Posted July 10, 2025

By Sean Ring